Last Friday brought an unexpected surprise. Earlier in the week, Michelle Gerling had accosted me in the middle of a conversation about GPS traces and aerial imagery at the Vovito coffeeshop in Bellevue, where a couple of us were rudely blocking the aisle with our open laptops and talking over each other as usual. She accused us of the usual sin, “having no life”, for talking shop instead of drinking cappuccino. (Although we were in fact also drinking cappuccino.) I rose to the bait and issued a two-pronged retort amounting to a) we’re on the eastside, not in Seattle, and b) what we’re doing is legitimate and creative coffeeshop activity.

Last Friday brought an unexpected surprise. Earlier in the week, Michelle Gerling had accosted me in the middle of a conversation about GPS traces and aerial imagery at the Vovito coffeeshop in Bellevue, where a couple of us were rudely blocking the aisle with our open laptops and talking over each other as usual. She accused us of the usual sin, “having no life”, for talking shop instead of drinking cappuccino. (Although we were in fact also drinking cappuccino.) I rose to the bait and issued a two-pronged retort amounting to a) we’re on the eastside, not in Seattle, and b) what we’re doing is legitimate and creative coffeeshop activity.

In the end this led to Ido dropping a very odd book off in my office at Michelle’s behest, accompanied by a typically understated note,

Hi Blaise,

My wife decided you must read this book I placed on your desk.

(if you are not interested, I can keep it with me for a week and tell her you really enjoyed it...)

‑Ido

Michelle explained at more length,

Your argument was the first of the kind I had heard from a ‘local’ that actually connected space, content and creativity.

For the past 50-odd years [sic] I have been writing a thesis that discusses similar connections– only in Beijing, and with a bunch of ruins as the center of discussion. That evening while ‘writing’, I needed a reference from the book I gave you, of course, instead of just searching and closing the book I started reading it for the millionth time– anything is better than actually writing a thesis, really.

Anyway, what you said came up while I was reading, and I asked Ido if you were the one who liked Hockney’s documentary. That was it basically.

I’m glad you find it interesting, it is an excellent book, very relevant to many discussions going on today about the way things are done in China.

[...] the copy you have is pirated. I had it photocopied at the local copy-sweatshop at Beijing University. Coffee & beverage stains are all authentic and were made by myself and several friends. Respect.

Enjoy reading it, my advice is that you should do so at a cafe in the eastside, so as to introduce the concept of originality where it is so lacking. It will also ward off people who want to talk to you about work.

Well, this book was indeed excellent as advertised, though it warded off no one. The central theses can be summed up so:

It’s a truism that Chinese art embodies a very different system of values from Western art. (We leave aside for the moment the difficulties arising from the very different definitions of art in China and in the West, and how these have evolved through the centuries.) While in the West reproduction is typically seen as art’s opposite, Chinese art has been characterized for millennia by processes of mass-manufacture, standardization of components or “modules”, factory production methods, and carefully constrained variability within archetypes. The result is a kind of biomimetic production system– hence analogies like the ten thousand leaves of a tree, all patterned the same way, but no two precisely alike.

Ledderose makes a provocative and possibly novel claim about such production systems: that the mother of them all is the Chinese writing system.

Characters decompose into strokes, which one can interpret as modules (between 8 and 70-odd, depending on how one clusters– the scheme shown above is a popular one from Liu Gongquan, 778–865). Through recombination and variation, one can form the tens or even hundreds of thousands of ideograms. I found this passage intriguing:

The Chinese found a middle way between the extremes of reduction to the mathematical minimum and boundless individuality. In their characters the average number of strokes is higher than four, and they did not set them into neat quadrants. Rather, they allowed for a great variety in size and relative position of the strokes. The character system has to be more complicated than mathematically necessary, because the human brain does not work like a simpleminded computer. An essential part in all perception processes is the recognition of known elements. [...] It is easier to remember slightly more complex shapes in which some parts are familiar than shapes in which the repetition is reduced to a minimum. If we miss a bit of the information, recognition of familiar forms allows us to grasp the meaning of the whole unit all the same.

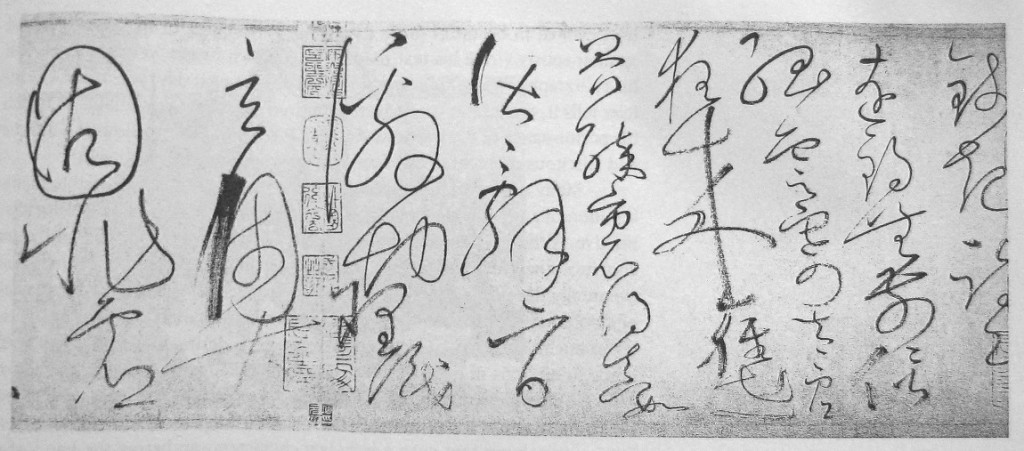

For “repetition” I’d use “redundancy”, but this is otherwise a fairly clear information-theoretic argument about the tradeoff between compression and error correction. Perhaps Chinese script is near something one could characterize as an optimum of sparsity for human visual processing? Perhaps one could think about the most extreme cursive scripts, like the example I’ll paste in shortly from Huaisu, as perturbations that probe the limits of the error-correcting cells?

Let’s now shift from grammar to semantics. Rather than accepting the European model of a China far ahead of its time 2500 years ago but in a kind of intellectual stasis ever since, Ledderose argues that the longevity of certain aspects of Chinese culture owes much to the longevity of modular production systems, which in turn owes its longevity to the historical continuity of the character system, as both an embodiment of the concept of modularity and a medium for its transmission. Because characters are signifiers of meaning rather than phonetic representations, they have a staying power lacking in Western languages. Pronunciations evolve; semantics don’t.

[...] an educated Chinese can read most texts written in all parts of the empire at any time in history, be it hundreds, even thousands of years ago. Script in China thus became the most powerful medium for preserving cultural identity and stabilizing political institutions. And if one wonders why the bureaucrats in Brussels have not yet been able to unite Europe, the answer may be that they use an alphabet.

I think there’s something here, though each claim on its own is falsifiable. The semantics of characters do evolve, and when spellings are standardized, phonetic languages drift while their written representations remain fixed, or we wouldn’t have words in English like “enough”, “wry”, and “knight”. (Indeed, it seems likely that English, as standardized today, is well on its way to being a worldwide and long-lived “language of empire”, though today the empire in question is the global economy.) The powerful and long-lived centralized political power of China has certainly reinforced the writing system, and benefitted from it in return, but the same was true of Latin for the Roman empire. If Rome had held together, would we have a “European China”, advanced yet somehow static, as envisioned by many writers of alternate history pulps?

The main body of the book is organized into chapters treating specific modular systems: ideograms, bronze casting, terra cotta armies, art factories, buildings, printing, and sets of paintings literally depicting “The Bureaucracy of Hell” (produced in the 13th century in what is now the Zhejiang Province). The book closes with a chapter called “Freedom of the Brush?”, in apparent counterpoint to the relentless modularity of the previous chapters. Using encyclopedias and aesthetically-motivated collecting as reference points, it delves into definitions of art in China, which historically center on calligraphy— in the West, considered only a minor “lowercase a” art. The literati defined this art in terms of the ideals of “spontaneity” and “naturalness”, emphasizing personal expression, even to the point of idiosyncrasy or madness— for example,

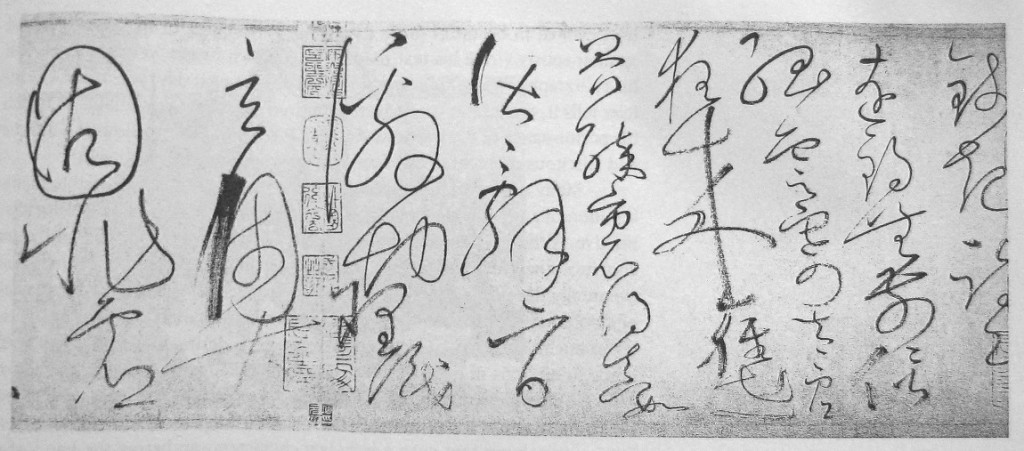

Huaisu embodies this ideal in his Autobiography, with his gorgeously fluid “Mad Cursive Script” (kuangcao) and matching personality, romantic in the sense of Byron or Van Gogh. The evident “action” of such painting inspired Robert Motherwell, Cy Twombly and Jackson Pollock, but Ledderose points out the obvious difference. As wild as Huaisu’s Autobiography is, it remains a text, because the strokes convey, however kinetically, a discrete and meaningful physical grammar. If one is a fluent writer in Chinese, these characters are legible, in the same way that an opera singer’s melody is perfectly clear to us even during long, complex runs in which tremolo varies the vocal pitch over a compass greater than the scored intervals. The singer isn’t creating splatter art, but performing a piece with well-defined notes. Likewise Huaisu’s art is the “performance” of a text in characters– the embodiment of a modular system. The variation and flavor of the performance is like tremolo, or rubato, clothing the underlying formal and semantic structures with rich personality but never obliterating them.

Interpreted one way, this implies that the ideals of literati art in China are more geared toward performance than composition. A piece of calligraphy may be prized as unique, but will be characterized this way not because of the content, but because of the inspiration immanent in and evoked by the performance of a particular artist, at a particular time and place— like Glenn Gould’s 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations. “A”, but also “the”. Jazz standards are another contemporary example, perhaps more fitting, since we tend to connect a piece much more with the artistry of a performer than with the original composer. My Funny Valentine: Richard Rodgers or Chet Baker? Body and Soul: Johnny Green? No, rather, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Coleman Hawkins.

Although the literati scorned factory and artisanal production, like that embodied by the mass-manufacture of tomb figures, the same principles of modularity together with variation apply there. Our Han tomb figures, which an old friend of Adrienne’s nicknamed Ping and Pong, are examples:

Ping and Pong had tens of thousands of brothers, yet each has a personality, rendered by artisans exploiting intentional degrees of freedom and variability in an otherwise efficient mass-production assembly line.

There seems to be a well-established Western tradition of curiosity, to put the finger on those points where mutations and changes occur. The intention seems to be to learn how to abbreviate the process of creation and to accelerate it. In the arts, this ambition can result in a habitual demand for novelty from every artist and every work. Creativity is narrowed down to innovation. Chinese artists, on the other hand, never lose sight of the fact that producing works in large numbers exemplifies creativity, too. They trust that, as in nature, there will always be some among the ten thousand things from which change springs.

Some profound questions about scale, context, creativity and agency emerge from thinking about these things, which is why this blog post has ballooned. If a naïve Western art critic were to unearth Pong as an isolated artifact, he might conclude, “wow! Giacometti had a Chinese twin!”. Of course we know that there was no Chinese Giacometti; yet soldiers in Ping and Pong’s armies are still sold at Southeby’s and regarded as art objects, alongside minor but “unique” works by famous European and American artists. If we follow Pong back through the years, through the hands of the tomb raiders, into the dark of the underground processional halls and back out again, when does their unmoulded clay touch the hand of the “artist”? It doesn’t– and not just in the sense that glass anemones from the Hotshop never pass through Chihuly’s hands. The “artist” is the entire production system, and that system has no clear boundary. It’s like nature– or rather, it is nature.

The ten thousand things are produced and reproduced, so that variation and transformation have no end.

– Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073), Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate Explained

Scott Morrison posted a good article today in the Wall Street Journal about our hire of Steve Coast, OpenStreetMap’s founder, and our announcement a week ago that we’d be sharing aerial imagery with OSM. OpenStreetMap, in case you don’t know, is a sort of Wikipedia for maps, contributed to by all, owned by all. It’s been up since 2004.

Scott Morrison posted a good article today in the Wall Street Journal about our hire of Steve Coast, OpenStreetMap’s founder, and our announcement a week ago that we’d be sharing aerial imagery with OSM. OpenStreetMap, in case you don’t know, is a sort of Wikipedia for maps, contributed to by all, owned by all. It’s been up since 2004.