I began keeping notebooks at age 7 or 8. My parents must have sent this one in a box a while ago.

The entries in it date from late 1985 to early 1986, so I would have been 10 at the time: a little pudgy, with an overbite, a bowl cut, and a very serious expression. It’s funny how clearly I remember this object.

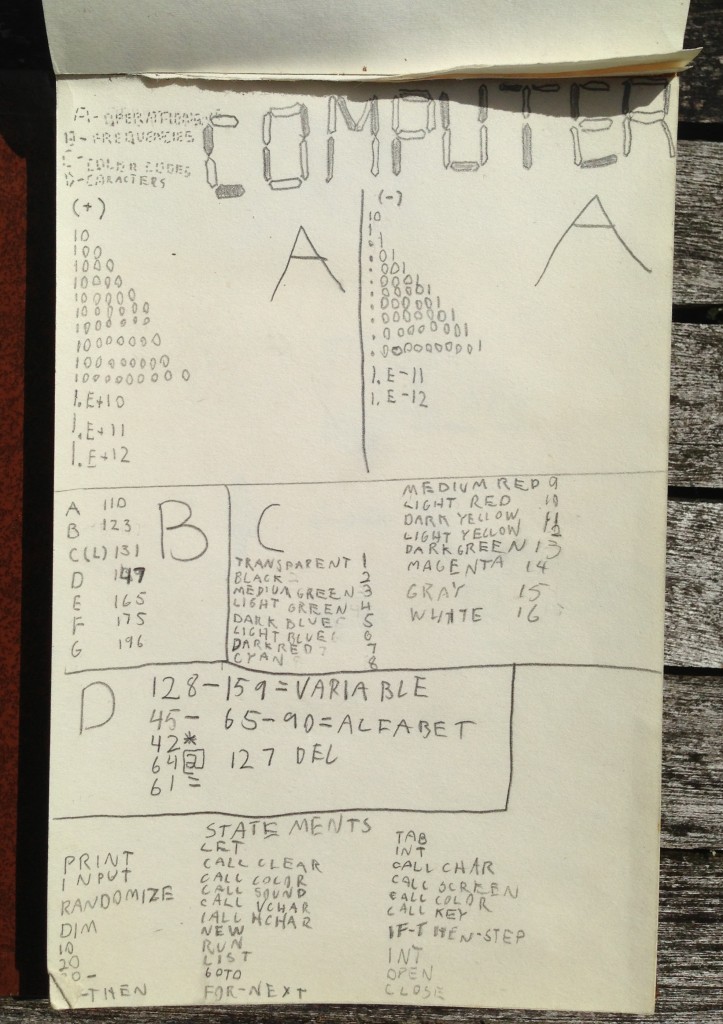

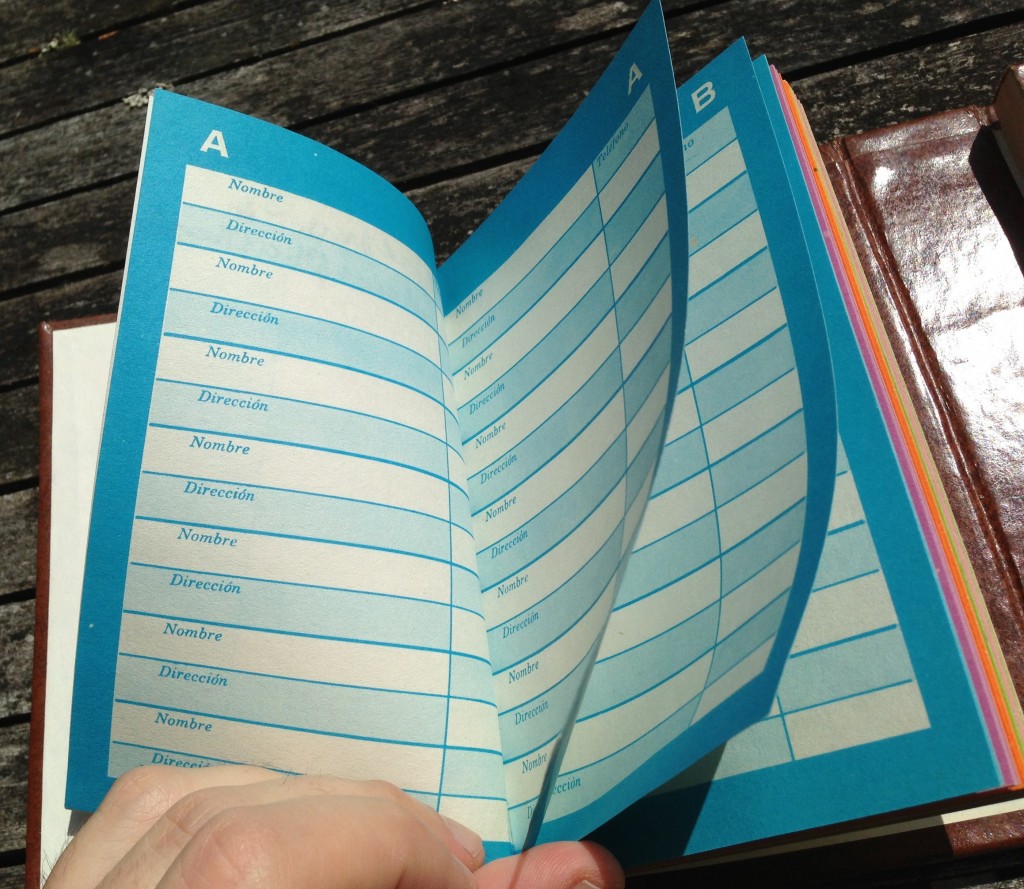

I asked my parents if we could buy it because I liked its pseudo-Edwardian design— and I liked the idea of a reference notebook of this size, with one side a directory of contacts and the other a pad of blank paper where I could keep track of the things that really mattered to me. Like resistor codes, colormaps, note frequencies, programming keywords and ASCII tables:

I asked my parents if we could buy it because I liked its pseudo-Edwardian design— and I liked the idea of a reference notebook of this size, with one side a directory of contacts and the other a pad of blank paper where I could keep track of the things that really mattered to me. Like resistor codes, colormaps, note frequencies, programming keywords and ASCII tables:

In truth this was a theoretical exercise, because I knew all of this stuff like the back of my hand. It was such a significant part of my little private universe, as familiar as the layout of our apartment and the graffiti scratched into my school desk.

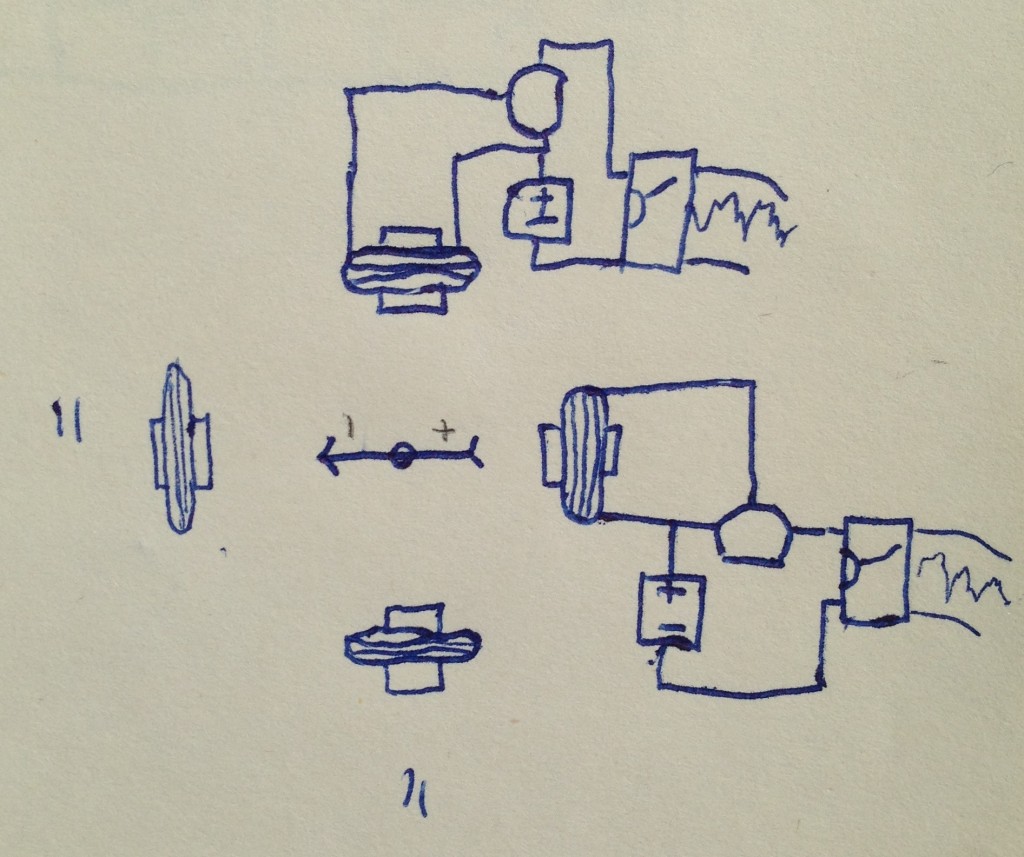

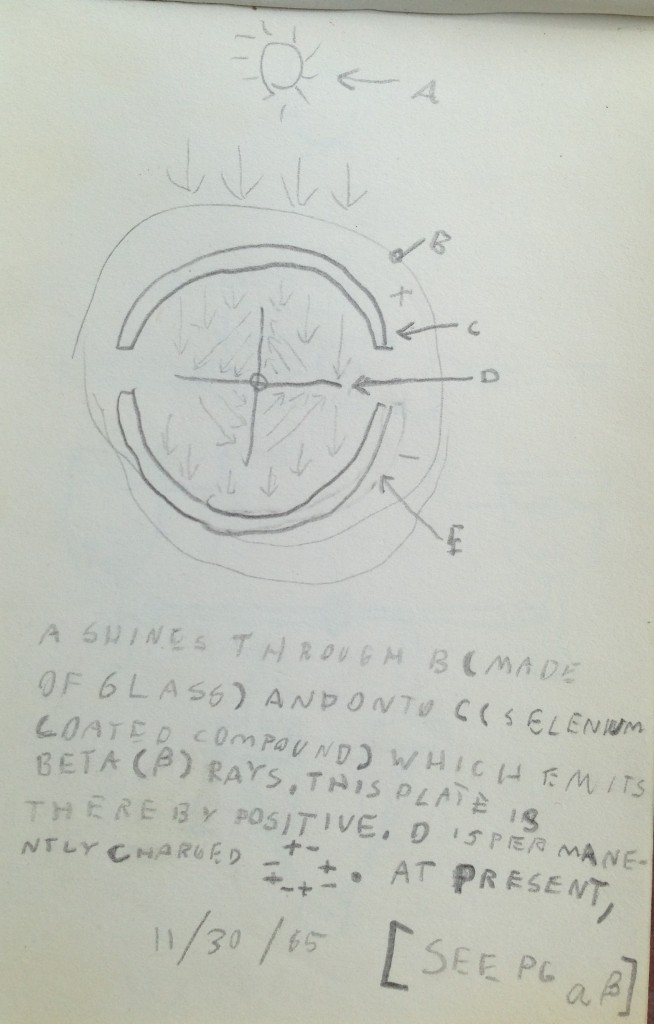

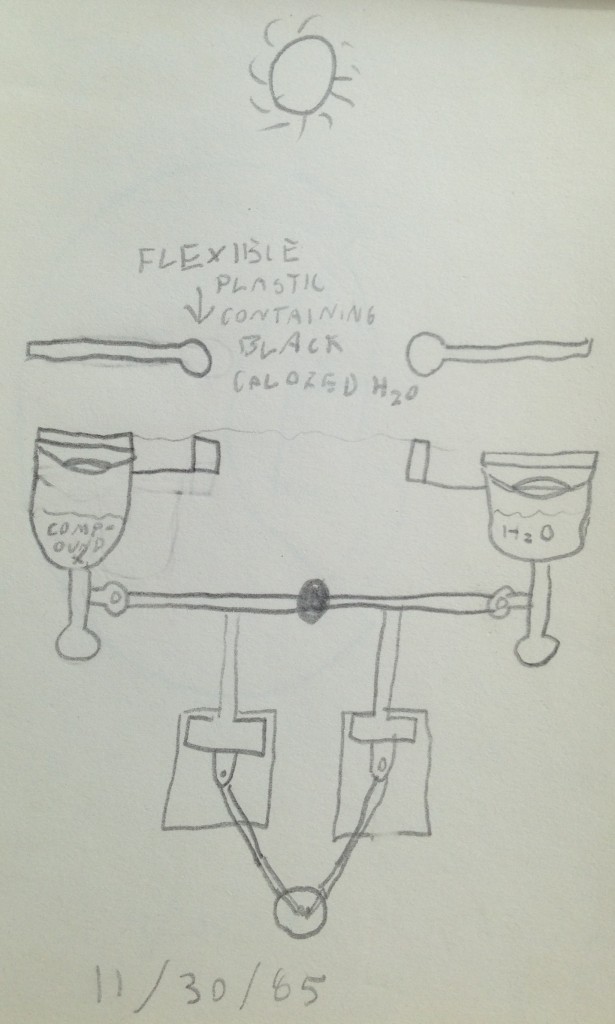

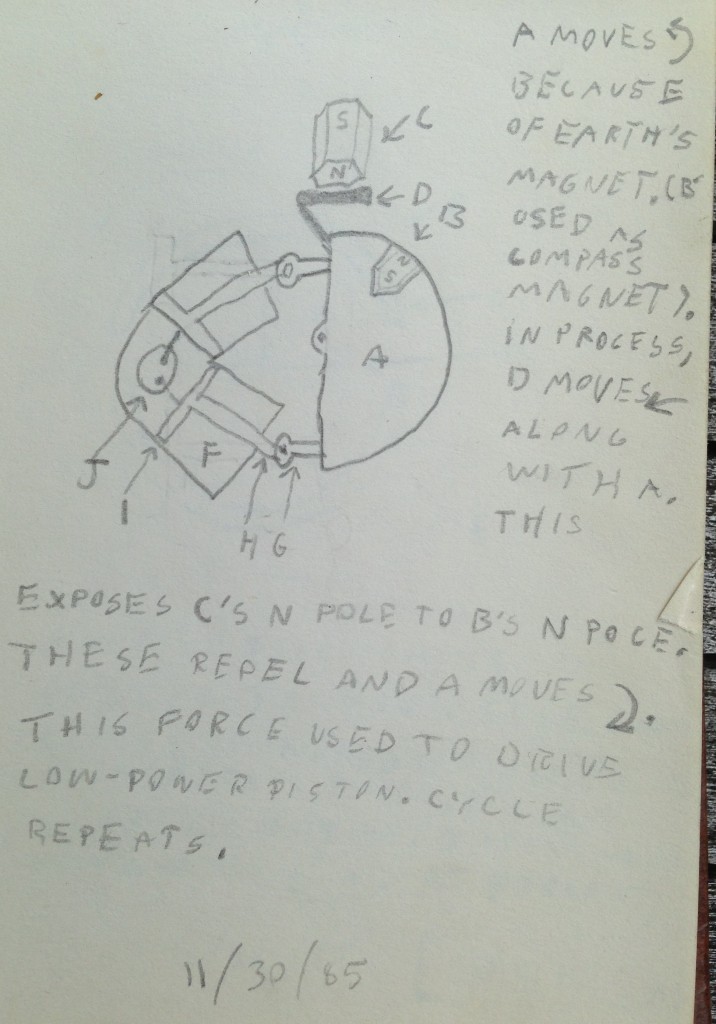

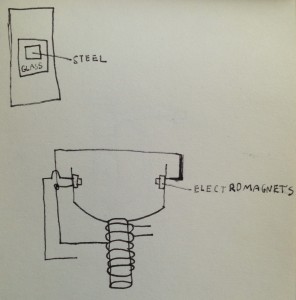

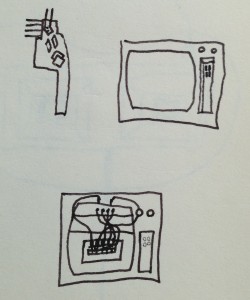

So in the next pages, reference tables quickly give way to notes and inventions, realized to different degrees. I was obsessed with electromagnetism, which is unsurprising in retrospect. Many of my obsessions were about the transduction of things unseen— usually current in wires— into the tangible, and vice versa. Anything that might mediate or interconvert between electricity and something that could be seen, felt or heard was interesting.

So in the next pages, reference tables quickly give way to notes and inventions, realized to different degrees. I was obsessed with electromagnetism, which is unsurprising in retrospect. Many of my obsessions were about the transduction of things unseen— usually current in wires— into the tangible, and vice versa. Anything that might mediate or interconvert between electricity and something that could be seen, felt or heard was interesting.

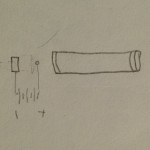

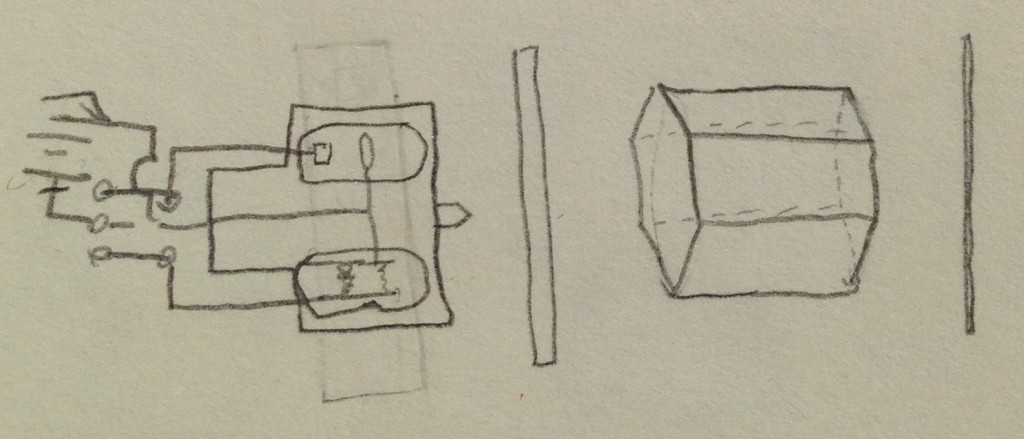

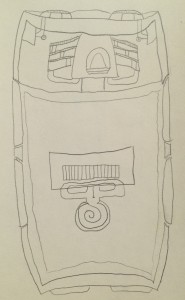

This was an application to something like an electrometer or magnetometer— I imagined that the compass would swing toward north if magnetized, or the charged needle align with an ambient electric field, and the inductors would generate currents that would allow the vector to be read out. It was inspired by the coils in speakers, and a voltmeter I took apart.

This was an application to something like an electrometer or magnetometer— I imagined that the compass would swing toward north if magnetized, or the charged needle align with an ambient electric field, and the inductors would generate currents that would allow the vector to be read out. It was inspired by the coils in speakers, and a voltmeter I took apart.

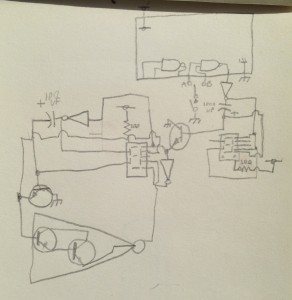

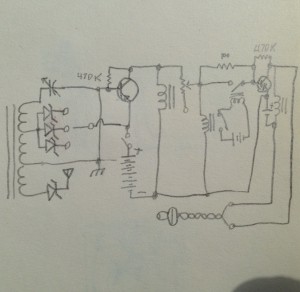

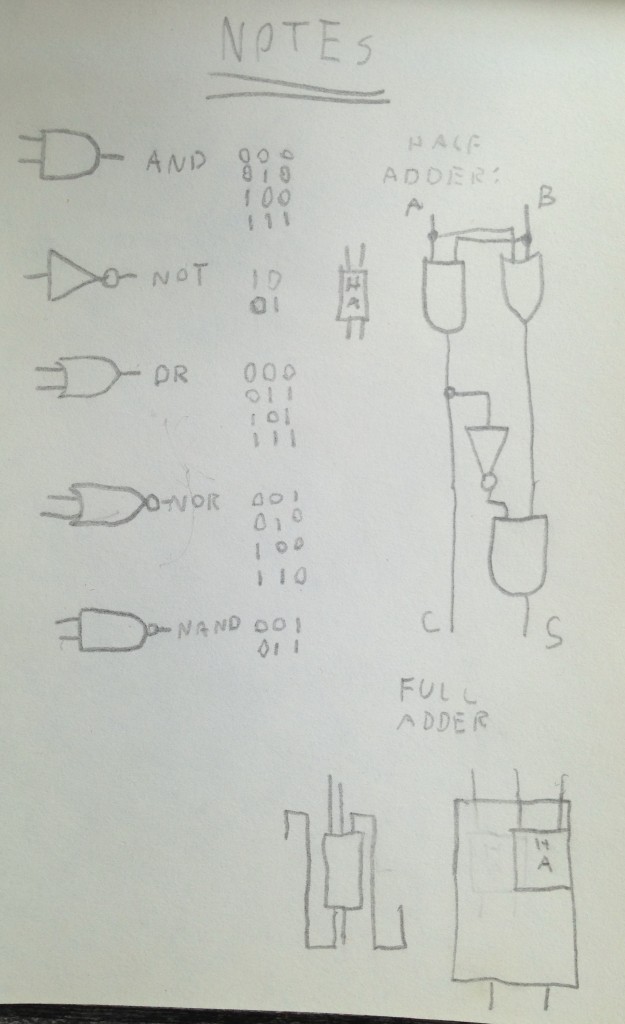

I had a 200-in‑1 electronics kit, and was especially enchanted with the couple of primitive chips on there— including such wonders as a quad NAND gate. The kit had a book full of circuit designs, which I disdained to build as written (though in frustration, when my own designs didn’t work, I would sometimes try to appropriate them by redrawing the circuits without looking at the original).

I had a 200-in‑1 electronics kit, and was especially enchanted with the couple of primitive chips on there— including such wonders as a quad NAND gate. The kit had a book full of circuit designs, which I disdained to build as written (though in frustration, when my own designs didn’t work, I would sometimes try to appropriate them by redrawing the circuits without looking at the original).

The crystal set radio was a mainstay, though the only way I ever got this to work was by stringing up a giant antenna, and could only ever pick up one station.

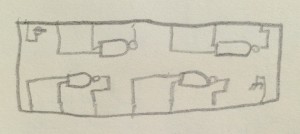

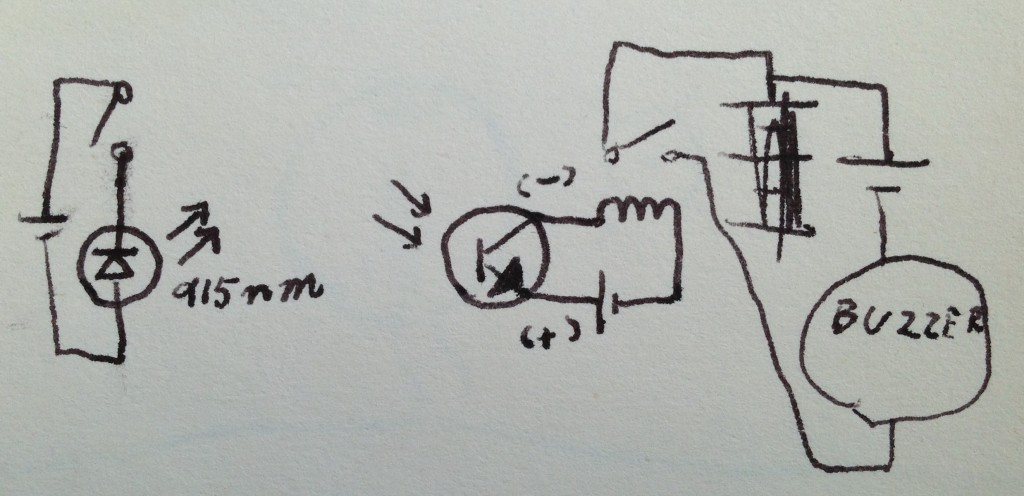

This was a simple but important circuit: an alarm designed to go off if my parents were in the hall. I taped the phototransistor just above cat height. For many years I insisted on total privacy while “working”, and hated to be interfered with. Part of the reason was that there was generally something taken apart in the room that should not have been, perhaps even something not strictly mine. But I also just really liked to be left alone.

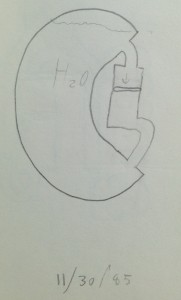

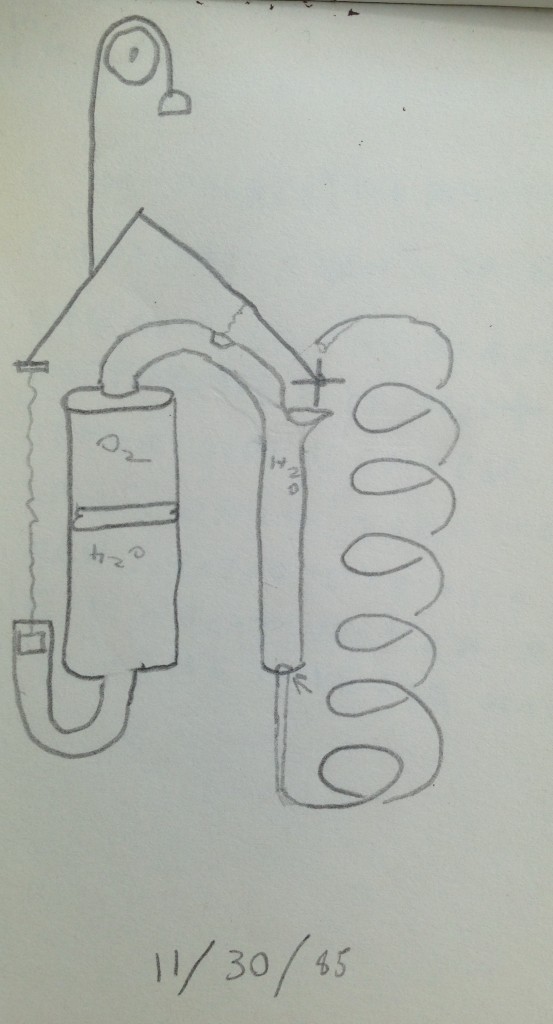

Mexico City’s water was undrinkable. I wanted to purify it with a still, or maybe by electrolyzing it and recombining the hydrogen and oxygen.

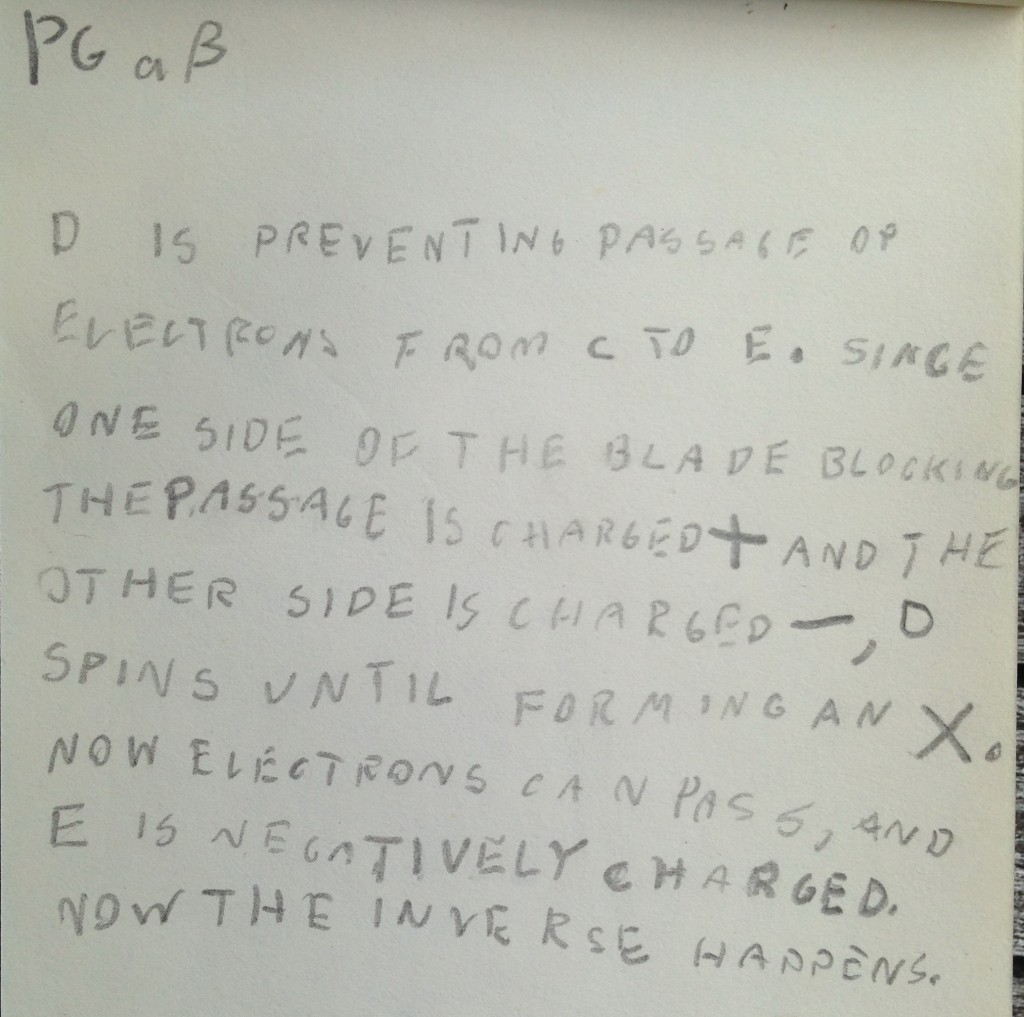

As some of these designs were solar, this led to thinking about solar power generation. I imagined beautiful glass balls on top of buildings with spinning rotors inside, eliminating the need for a power grid.

But in my heart I worried about the efficiency of generating power by knocking electrons off of the doped selenium.

This was a more direct approach, based on something like a Stirling engine. Slowly reciprocating pistons would drive a generator.

At this point I wondered why the same couldn’t be done with the Earth’s magnetic field. I was very excited by some of these ideas and began talking about them with adults. At this point the term “perpetual motion machine” entered my vocabulary. I struggled with the difference between force and energy, and remember finally getting it— or thinking I had— with a conceptual diagram involving something like a piston in the handle of something like a gallon milk jug. Though admittedly I’m finding the logic a little unclear now.

At this point I wondered why the same couldn’t be done with the Earth’s magnetic field. I was very excited by some of these ideas and began talking about them with adults. At this point the term “perpetual motion machine” entered my vocabulary. I struggled with the difference between force and energy, and remember finally getting it— or thinking I had— with a conceptual diagram involving something like a piston in the handle of something like a gallon milk jug. Though admittedly I’m finding the logic a little unclear now.

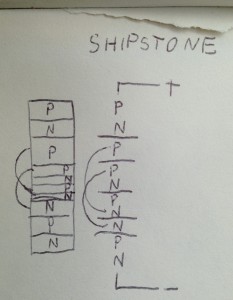

I was frustrated with batteries. There were no rechargeables around at the time. After a few accidents, I was leery of drawing power from wall sockets, and there were always drawerfuls of spent batteries lying around. It was wasteful; and worse, batteries seemed to me so clearly just toys, not a real part of the energy infrastructure. I was reading a lot of Heinlein at the time, and the idea of a super-efficient battery that could power a whole house— the Shipstone— was impossibly appealing. I desperately wanted to be Daniel Shipstone and invent this thing. Maybe with some kind of semiconductor doping?

I was frustrated with batteries. There were no rechargeables around at the time. After a few accidents, I was leery of drawing power from wall sockets, and there were always drawerfuls of spent batteries lying around. It was wasteful; and worse, batteries seemed to me so clearly just toys, not a real part of the energy infrastructure. I was reading a lot of Heinlein at the time, and the idea of a super-efficient battery that could power a whole house— the Shipstone— was impossibly appealing. I desperately wanted to be Daniel Shipstone and invent this thing. Maybe with some kind of semiconductor doping?

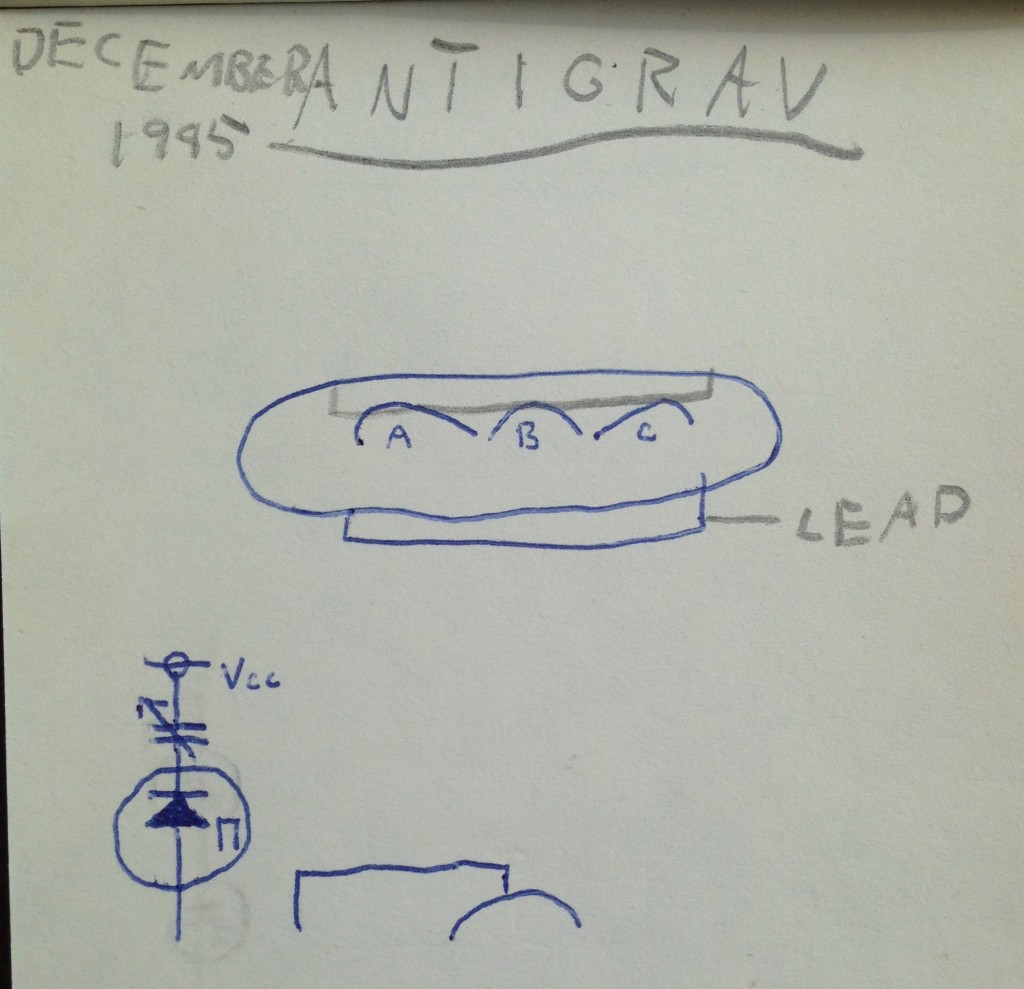

Those kinds of flights of fantasy veered into super-powerful lasers, or antigravity machines.

Wishful thinking, in other words. This made me angry with myself, because it was clearly not “working”, not coming up with real stuff. Which is what I always insisted I was doing, locked up in my room. Shipstones and antigravity machines that couldn’t operate on any principle I knew of were just play, and I was acting like a child. The look of tolerant amusement in the librarian’s eyes when I explained a fanciful invention drove me into a quiet rage. I didn’t want to think of myself as a child, and loathed childishness, and pretty much loathed most other children.

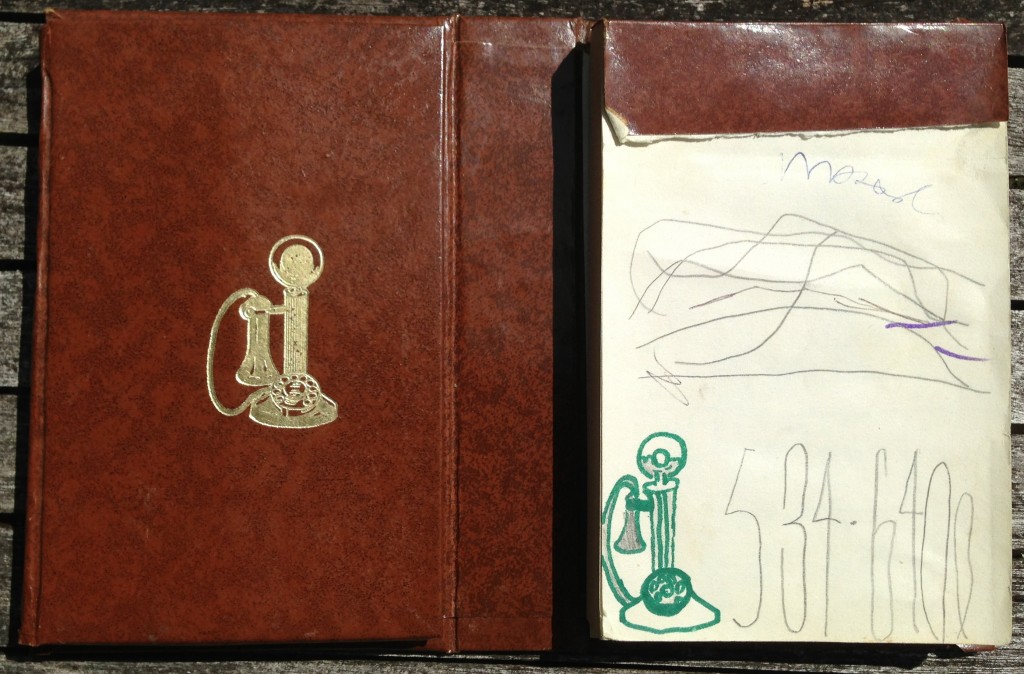

In retrospect it seems clear that a lot of this was due to other children’s discomfort with me, and my inability to fit in socially. I was so odd, so alien, so easy to make fun of— and I was desperate to be the one who did the rejecting first, rather than risk being the one who was rejected. This gave me a kind of aloofness, hence immunity to the hurt of isolation... but of course it was also a vicious cycle, since this attitude hardly helped endear me to my classmates. Maybe that’s why the whole phone directory side of this notebook stayed pretty much empty—

Well, not totally empty. There was Luis, who may or may not have been a high school kid in my mom’s art class whom I got on with, and the other ‘L’, a purveyor of electronic components.

There are only one or two other entries in the addressbook. I wrote this “human stuff” in cursive, because its inherent sloppiness seemed more fitting; block lettering was reserved for real things.

So, better to be alone, and to be an adult-child. With grim pleasure, I’d get back to “work”. On real things.

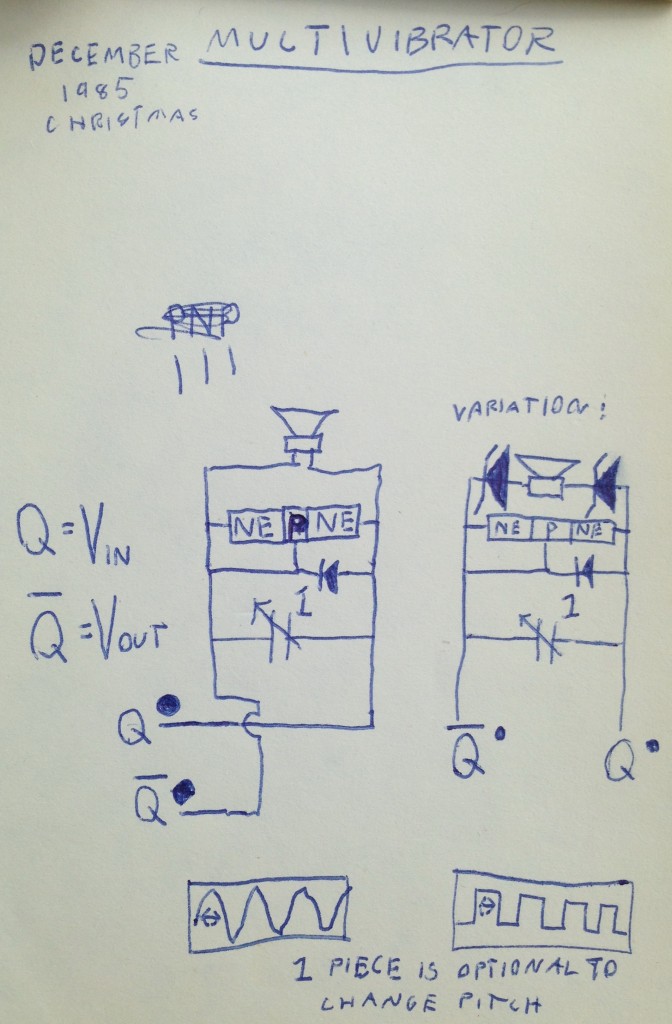

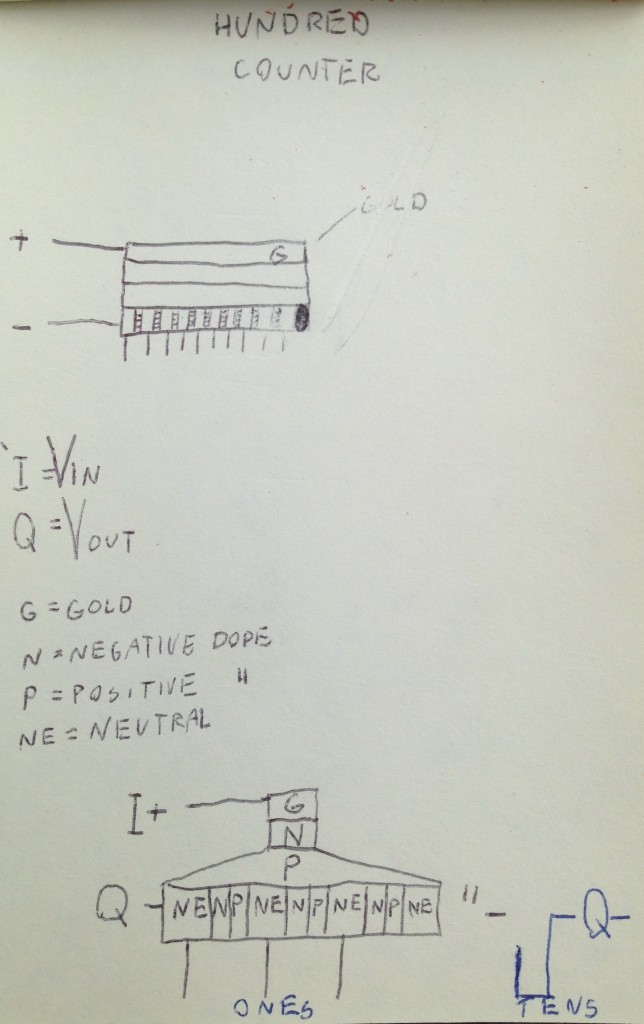

Computers were more real. I’d had one in my room since 1981. Though I still thought there had to be better ways of implementing their building blocks, things like multivibrators and counters. I imagined doing it with tunnel diodes and specialized silicon instead of gates. Really this was something like a design for base-10 transistors.

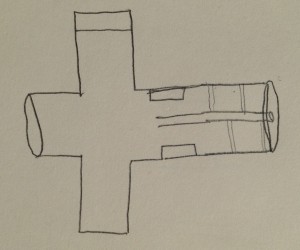

Vehicle design was another passion. I thought that a “convertible” meant a car/boat (a James Bond inspired misconception), and remember being very disappointed by how little was really meant by the word. The “turbo” in this car could either recover energy from the exhaust or be used to propel it like a squid.

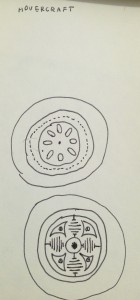

I thought planes might be more efficient and make less noise if they were shaped like hollow tubes, with more slowly rotating fan blades inside. The passengers could sit in the wings. And what kind of engine could a hovercraft have?

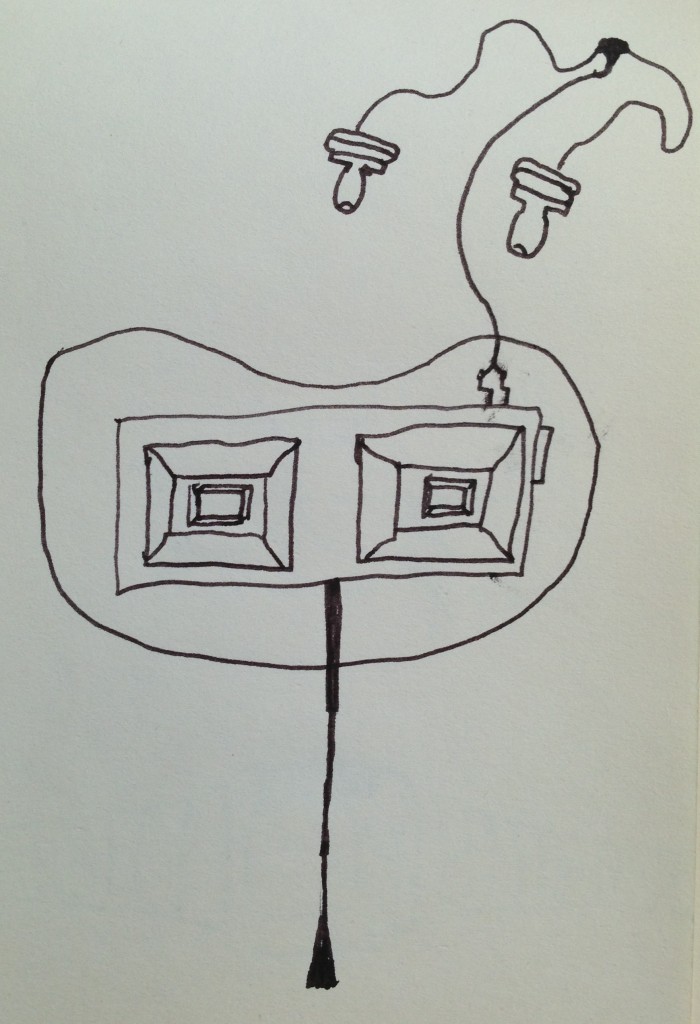

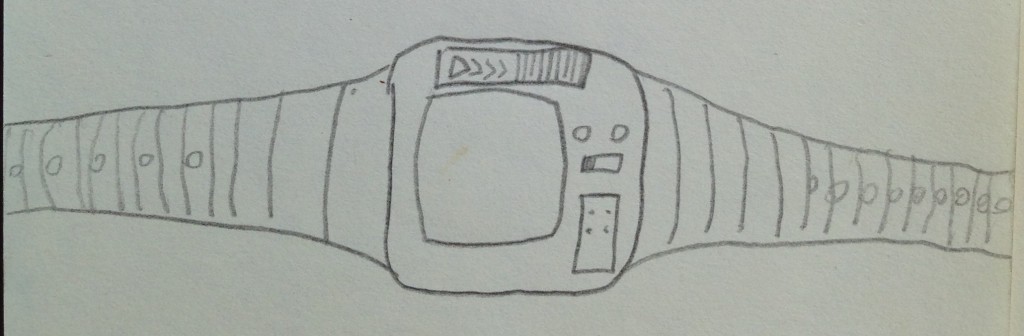

But this was again veering toward the unconvincing. I wanted to solve a real problem in a real way, like the unacceptable design of the cathode ray tube.

It was essential to flatten and miniaturize it. Why could the electron gun and plates not be arranged on a steep angle? The point being, of course, wearable computing.

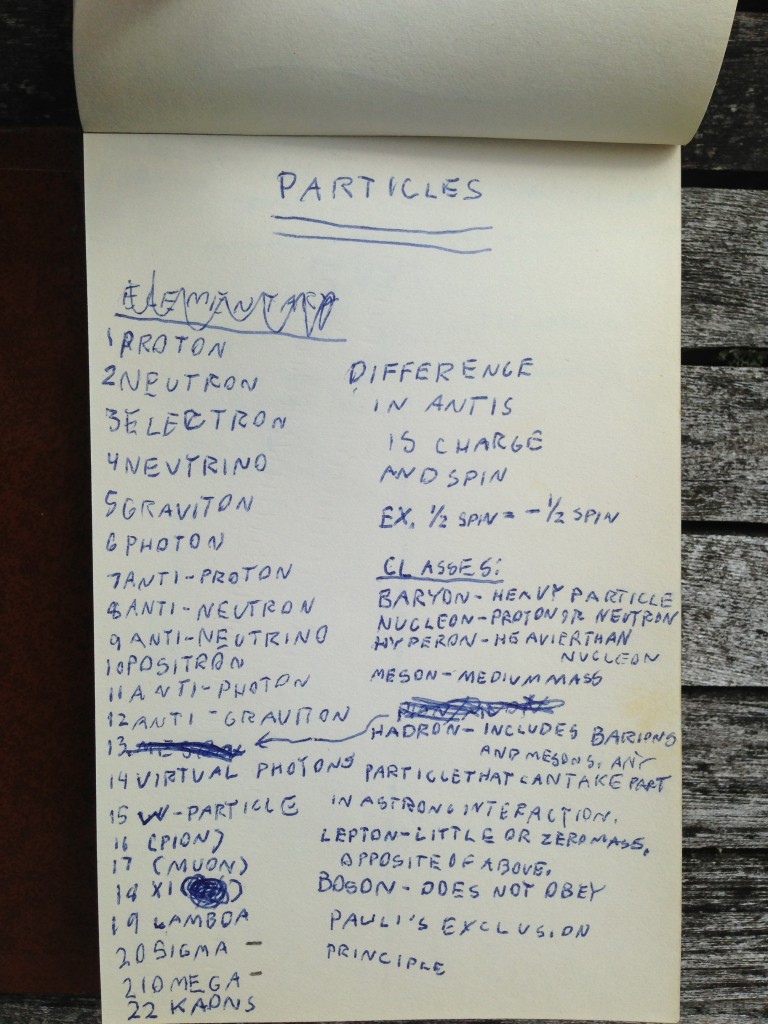

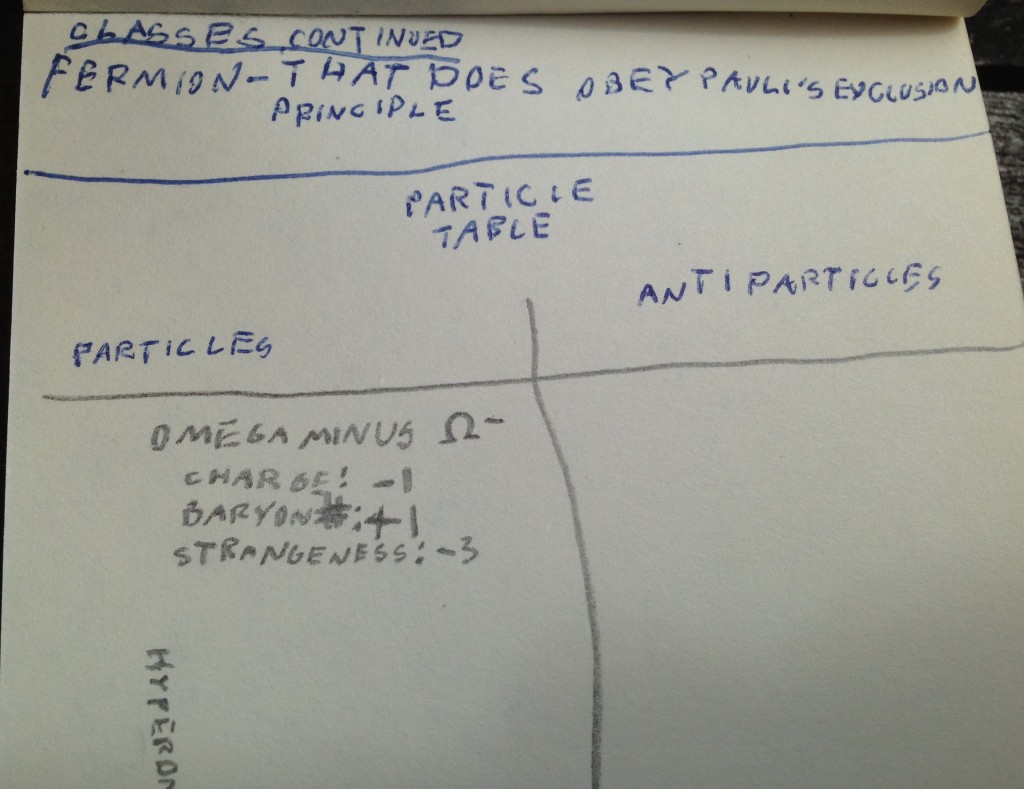

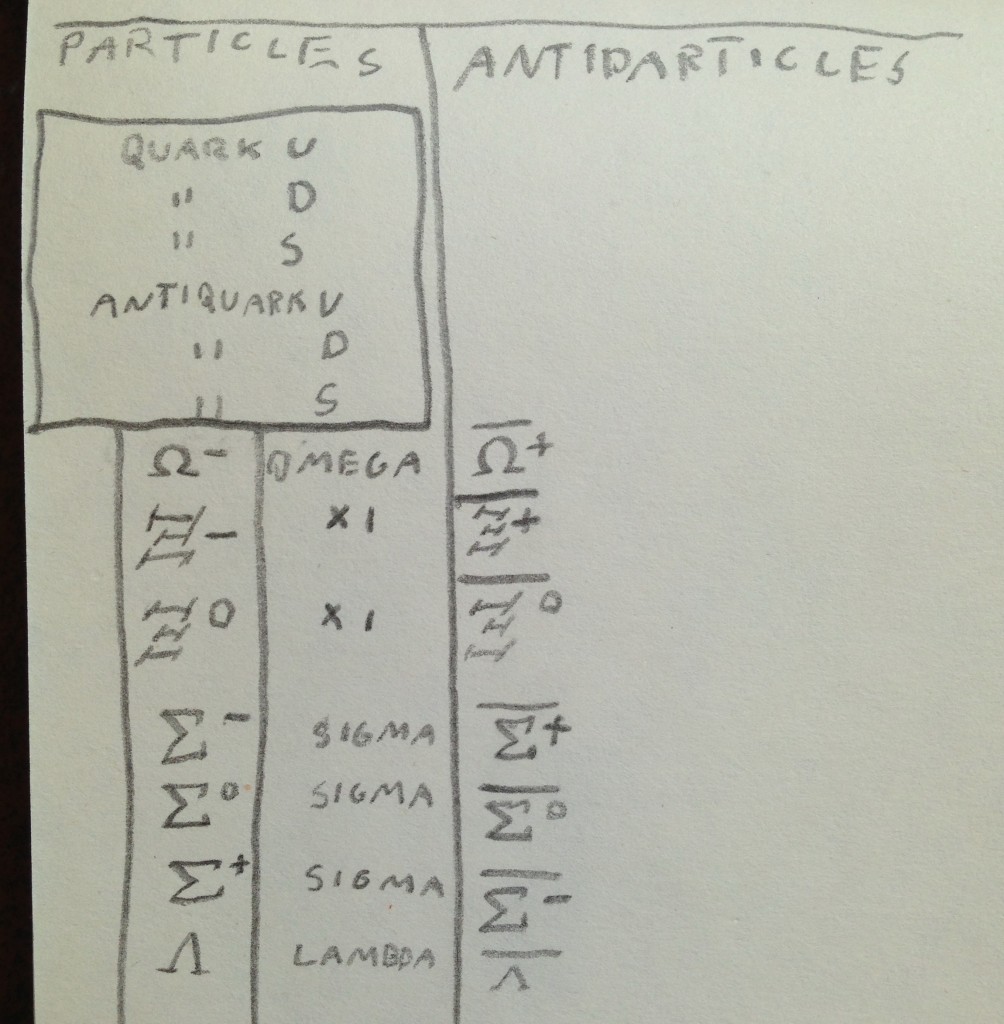

Toward the end of this notebook, I’m focusing on pure physics, trying to find good ways to tabulate the fundamental particles.

One might suppose this was because I realized that a training in physics would be important in order to become a real inventor. But actually, something more problematic was going on. I felt that there was a hierarchy of seriousnesses among my interests, and that physics was the most serious thing. Physics was about the fundamental nature of everything, not just some transient engineering problem or— worse— something merely human. I imagined that things like the electric motor, while not really physics and therefore far from fundamental, were likely to at least be fairly universal developments among the uncountably many advanced civilizations in the universe. Therefore not so bad to work on, right?— because if I were an alien I just might be doing the same thing. This kind of work was sort of species-invariant. More like physics. Not that I was able to put it to myself quite that explicitly.

But throughout these years and many that followed, I was developing a secret love of programming. Many other nerds growing up around the same time will know exactly what I mean when I write that nothing else could keep me so relentlessly, continuously and joyfully engaged in a problem. It let me experience flow, for hours and hours, and it was utterly addictive. Inventing on paper could produce a state of reverie and even elation for a while, but making physical things was always hard, always ran up against constraints. I’d run aground and need to call Larry and see if he had a missing part in stock. It was stop and go, everything always unfinished, the idea always realized crudely if at all. Maybe one day 3D printing, programmable biology or nanoassembly will really bring “making” into the same space as programming, but this still seems far off.

In any case, my love affair with the computer, while it could hardly stay a secret, was something I felt vaguely embarrassed about— because it was so far removed from the fundamentals of the universe. Because it was engineering, and worse, engineering with things that had themselves been engineered by other people. Second- or third-order. So not fundamental.

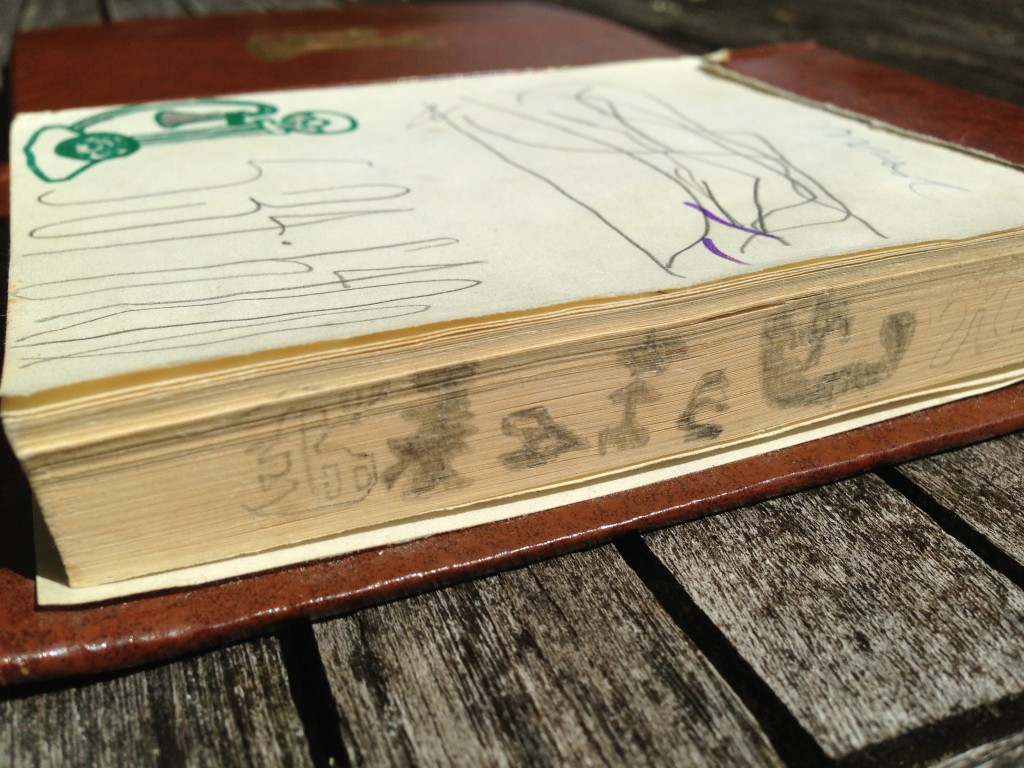

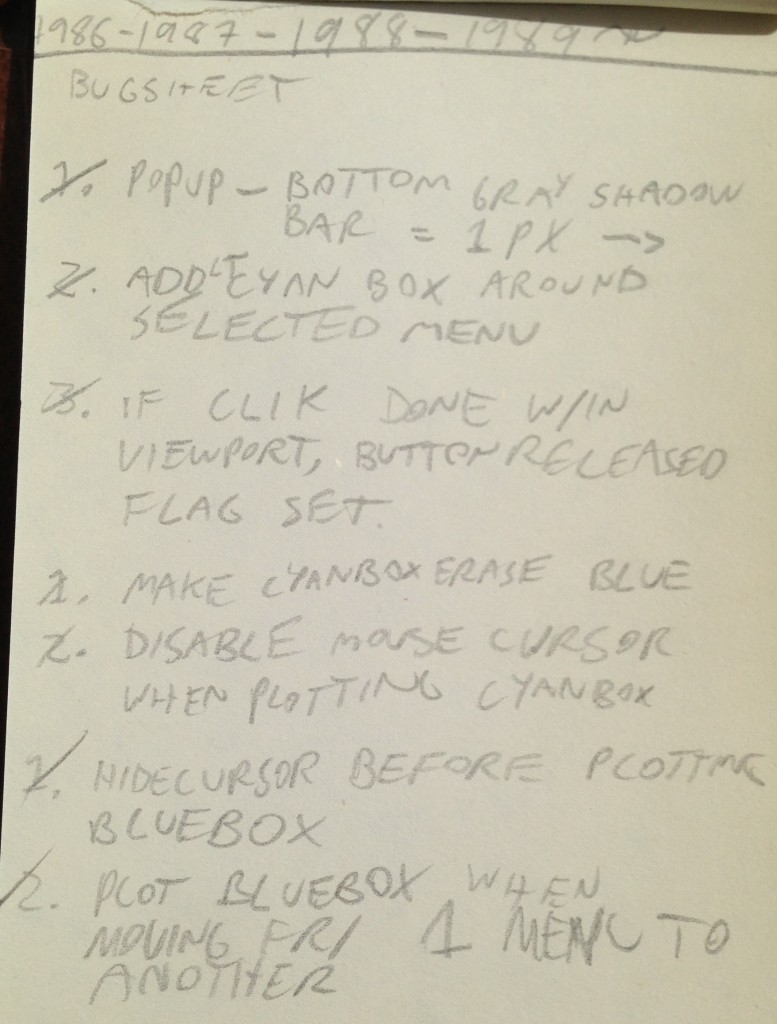

That’s why the very last page of this notebook, written sloppily, is a “bugsheet”— my way of tracking work items and bugs in the programs I was working on at the time. These were of course ephemeral for me. I thought the inventions were important to preserve, but these work items were more often than not scribbled on scratch paper. There are lots of pages torn out of this notebook, and I have a feeling that many of them were similar to this one. Looking at the bugs, I vaguely remember working on a windowing system at the time. (I guess this would have been around when Microsoft released Windows 1.0, though I didn’t encounter Windows until much later.)

For reasons I’m not entirely sure of, I wrote at the top of this page “1986 – 1987 – 1988 – 1989 ~ ”. This might have been a prediction about how long it would take me to build this ridiculously ambitious project, or— maybe I’m reading too much in now— a resigned sense that this part of my life was going to stretch out, and on and on, beyond the unimaginable future on the far side of puberty.

I’m sorry to say that my hierarchy of values was reinforced— matched perfectly, in fact— by many of the physicists I met later on, and by the culture of physics in general. I still love and respect the field, but with reservations. I don’t know of any other profession that embodies such casual, unarticulated chauvinism for such a broad range of human activity; everything else is too specific, too contingent, too easy, too manmade, too lacking in rigor. And then even within physics the hierarchy repeats in a self-similar manner, with this or that field above the other. Biophysics? Too squishy. Solid state? Too engineering‑y. Astronomy? Stamp collecting.

I’m glad I got out when I did, before things went really wrong in my life. I’ve recovered— mostly.

I’ve been extraordinarily lucky. First, I was lucky because my parents were so deeply supportive of me when I was young. They never laughed in the face of my utter, absurd and rather brittle seriousness. They encouraged me in every way without ever being patronizing, they drove me to faraway electronics suppliers in search of exotic components in the service of ill-specified projects. They smuggled computers across the border from the US. They pretended not to notice when remote controls went missing, and they gave me the space and time to develop in my own odd, lumpy way. They trusted me.

And in time, It Got Better: partly because the passions I’ve always had most authentically are constructive and happen to be in high demand. I can now admit that what I called “work” as a ten year old really was play; and that I still spend much of my life engaged in this kind of imaginative play; and that— in a delightful twist— I’m now paid to do it. I work with many people who had similar experiences as kids, and who have similarly found themselves welcome and valued in society as adults. We get to play together, and realize really big projects we could never do alone.

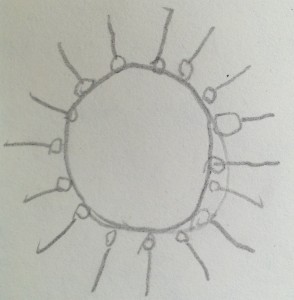

This sketch is the only one in the notebook of anything even remotely human or biological. I remember a sense of hopelessness at the sheer numerical impossibility of a spermatozoon ever finding and fertilizing the egg. I wanted there to be more than one winner.

The curdled feelings that used to lie in wait when I stepped away from the computer or the workbench, the intense sense of alienation and alone-ness I would try to preemptively embrace when I was 10, are mostly gone. It’s taken quite a few years. What a joy and relief it is to have close friends, to love and be loved, to be able to connect, and to feel, if not exactly normal, at least normal enough. Human.

17 Responses to notebook