Recently finished William Gibson’s new novel, Zero History, during the no-electronics phase of a plane’s ascent to 30,000 feet. It feels like I’ve read half of this book during takeoffs and landings.

Recently finished William Gibson’s new novel, Zero History, during the no-electronics phase of a plane’s ascent to 30,000 feet. It feels like I’ve read half of this book during takeoffs and landings.

I have a soft spot for Gibson. A good deal of my professional life has been about making cyberpunk real. He’s one of the visionaries who defined this field, and it’s a rare breed of writer who has not only perceived a hidden shape, and told a good story, but who has influenced the course of events in the real world through the revelation of that hidden shape.

However, this post isn’t a love letter. Yes, I enjoyed Zero History, though in a low-temperature sort of way. This wasn’t a book that made me stay up late, or prevented me from powering up my notebook on reaching cruising altitude.

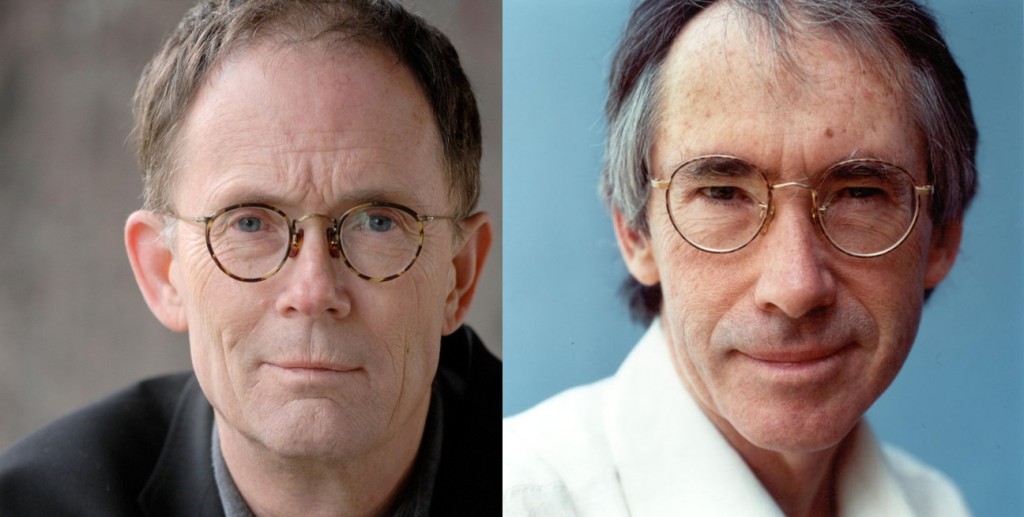

Gibson is at a comfortable point in his career, shifting gears smoothly while keeping that writer’s voice steady and assured. He sports an agreeably fit yet grizzled half-smile on the jacket photo. I’m sure he gives a great campus talk; he certainly reels off a fine quote, like

“The future has already arrived; it’s just not evenly distributed yet,”

a thought that’s been reproduced on ten thousand blogs. (Make that 10,001.)

Back when Gibson believed that the future might not have arrived yet, he was a shimmering, if uneven prophet. The writing was better than it needed to be, because the ideas alone were good enough. A couple of decades on, in éminence grise mode, he’s put away his VR goggles and donned tortoiseshells, taking on the more dignified role of commentator on the here and now— or his own personal version of it. The trouble is that where there used to be big ideas, there are now just peculiar obsessions. Consumer electronics and rare earths, for instance. And fashion, especially of the denim and Converse variety. Perhaps it’s always been there, but the off-axis wobble of these obsessions comes into very sharp focus when the society Gibson is describing isn’t a San Francisco of the imagination, but the world we supposedly inhabit.

This may sound odd, but I’m reminded of Ian McEwan. Like Gibson, McEwan once wrote some electrifying stuff (The Cement Garden and The Innocent come to mind). Then, in 2003, Saturday came out. There was plenty of critical praise, but a scathing critique from John Banville in the New York Review of Books:

Owning things is important to Perowne, an unashamed beneficiary of the fruits of late capitalism. Few passages catch the flavor of this extraordinary book as well as the one in which, apparently without a trace of authorial irony, Perowne is made to recall an epiphanic moment on a fishing trip when his eye lit on his beloved car, a “Mercedes S500 with cream upholstery”:

“Glancing over his shoulder while casting, Henry saw his car a hundred yards away, parked at an angle on a rise of the track, picked out in soft light against a backdrop of birch, flowering heather and thunderous black sky— the realisation of an ad man’s vision— and felt for the first time a gentle, swooning joy of possession. It is, of course, possible, permissible, to love an inanimate object [...]”

[...] Theo comes up with an aphorism: “The bigger you think, the crappier it looks,” and follows it with an apologia pro vita sua which we assume, mistakenly, as it turns out, Perowne, or McEwan, will challenge as vapid and self-serving:

“When we go on about the big things, the political situation, global warming, world poverty, it all looks really terrible, with nothing getting better, nothing to look forward to. But when I think small, closer in— you know, a girl I’ve just met, or this song we’re doing with Chas, or snowboarding next month, then it looks great. So this is going to be my motto— think small.”

It might also be, amazingly, the motto of McEwan’s book.

In his recent writing especially, Gibson also dwells lovingly on the small. Small, and preferably inanimate– materials, vehicles, clothes, accessories. The word “iPhone”, which embodies everything Gibsonesque, is used 55 times in Zero History. The normally more common word “face” is used only 35 times, after subtracting the nearly equal number of times it refers to watches and other artifacts. The phrases in which it occurs are interesting too:

“Blond, a face he’d forget as soon as he looked away”, “unused to inhabiting his own face”, “hide his face”, “wiping her face, mechanically”, “his face battered and immobile”, “imagining they see his face on coins”, “trousers in front of his face”, “Orwell’s boot in face forever”, “your basic pasty-faced Caucasian fuck”, “a hockey jersey with a face painted on it”, “a grotesque and enormous face. ‘Looks Constructivist,’ he said”, “half of his thin face lost behind an unwashed diagonal curtain”, and “we’ve had face time”.

So much for “face time”. On the other hand the word “jacket” is used, incredibly, 114 times, as in,

“mechanic jacket”, “denim jacket”, “leather jacket”, “cotton motorcycle jacket”, “mulberry wool Mugler jacket”, “short black jacket”, “Nice jacket”, “olive-drab jacket”, “black jacket”, “leather tour jacket”, “tweed hacking jacket”, “complexly black majorette jacket”, “tight short jacket, with its fringed epaulets and ornate frogs”, “black ‘Sonny’ jacket”, “inside-out jacket”, “crumpled cotton jacket”, “very old, very grimy insulated jacket with that Amstrad logo on the back”, “armored jacket”, “translucently ancient waxed cotton jacket over the tweed”, “majorette jacket open over an Israeli army bra”...

Now we feel the love!

Gibson and McEwan, both born in 1948, feeling at the top of their game.