The violin is in some ways a problematic instrument. I’ve always had mixed feelings about its popularity, the way it displaced its noble and diverse predecessors, the viols, its grasshoppery diva nature, its demand for virtuosity. I give the violin a lot of shit, but one really can’t argue with its emotional punch. There’s a reason why it’s such a successful invasive species, blanketing the musical landscape from Icelandic pop to Appalachian hoedowns to Karnatic ragas.

Here are four pieces of music that make me love this old enemy. Starting with the blindingly obvious,

Bach’s violin sonata in g minor, as performed by Schlomo Mintz. The sonatas and partitas are uniformly gorgeous, but my favorite is this first sonata. It’s technically challenging to pull off its many double and triple stops while still keeping the voicing clear, the rhythm solid, and most importantly keeping that secret fire lit that burns underneath Bach’s best stuff, that volcanic power. On the piano, nobody can do that like Glenn Gould, though I’d have to give Vladimir Viardo an honorable mention. On the violin, it’s Schlomo. This is maximal music for solo violin, a moment of flowering for the instrument that stretches it to its utmost potential and, in certain respects, beyond. It’s like an Old Master drawing executed in a single continuous stroke, without lifting the pencil off the paper.

Bach’s violin sonata in g minor, as performed by Schlomo Mintz. The sonatas and partitas are uniformly gorgeous, but my favorite is this first sonata. It’s technically challenging to pull off its many double and triple stops while still keeping the voicing clear, the rhythm solid, and most importantly keeping that secret fire lit that burns underneath Bach’s best stuff, that volcanic power. On the piano, nobody can do that like Glenn Gould, though I’d have to give Vladimir Viardo an honorable mention. On the violin, it’s Schlomo. This is maximal music for solo violin, a moment of flowering for the instrument that stretches it to its utmost potential and, in certain respects, beyond. It’s like an Old Master drawing executed in a single continuous stroke, without lifting the pencil off the paper.

(As a side note, the g minor works beautifully on Baroque lute as well, where many more notes from amongst the inner voices can be enunciated. It then becomes a different piece altogether, less spare, yet still expressive. One can think of the Baroque lute as a midpoint between the violin and the harpsichord. On the violin, both hands tend intimately to each note, with every analog nuance of fingering and bowing reflected in the sound. The harpsichord is “pure digital”, with every element of a performance reduced to a timing code. The piano is the modern answer to reintroducing analog into keyboard instruments, but it’s a very reductive, MIDI kind of analog: a single, perfectly measurable parameter per note, the speed of the hammer when it strikes the strings. With the lute, the left hand articulates the notes against frets, making it a “digital hand”, but the right hand is expressive in that infinitely subtle, continuous phase-space manner of the violin.)

Now we move back in time from 1723 to 1676, around the time of the emergence of the violin in the form we now know it, as a solo art instrument. The first great violinist and violin composer was Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber. And my pick #2 is:

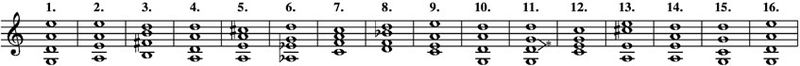

The passacaglia in d minor that concludes Biber’s Rosary Sonata cycle, sometimes called the Archangel Sonata. This cycle of fifteen “mysteries” has a place in my heart. Every sonata is preceded by a round engraving representing a bead from the rosary, and every piece is in a different tuning or scordatura, totally changing the tonality of the instrument. Some even involve swapping the middle two strings. The scores are written as if to be played on a normally tuned violin, making them read oddly and sometimes nonsensically on the page; the tuning must be discovered, and they must be played with blind faith, like prayers recited over the rosary beads. The resulting music of course doesn’t correspond to what’s written, falling in this sense somewhere between score and tablature.

The passacaglia in d minor that concludes Biber’s Rosary Sonata cycle, sometimes called the Archangel Sonata. This cycle of fifteen “mysteries” has a place in my heart. Every sonata is preceded by a round engraving representing a bead from the rosary, and every piece is in a different tuning or scordatura, totally changing the tonality of the instrument. Some even involve swapping the middle two strings. The scores are written as if to be played on a normally tuned violin, making them read oddly and sometimes nonsensically on the page; the tuning must be discovered, and they must be played with blind faith, like prayers recited over the rosary beads. The resulting music of course doesn’t correspond to what’s written, falling in this sense somewhere between score and tablature.

Only the first mystery and the passacaglia are in normal tuning. The passacaglia dispenses with the basso continuo accompaniment of the preceding sonatas. The solo violin begins with the four descending ostinato notes, G, F, Eb, D. The rest of the piece is based entirely on this bassline, spinning variation after variation. This highly constrained formula is hypnotic, transcendent, and somehow narrative in that way that variations can be when done perfectly. A melancholy sunset, brushed in slow and red over a northern sky. Meaning without meaning, a world within a dewdrop, minor key scales without end.

Only the first mystery and the passacaglia are in normal tuning. The passacaglia dispenses with the basso continuo accompaniment of the preceding sonatas. The solo violin begins with the four descending ostinato notes, G, F, Eb, D. The rest of the piece is based entirely on this bassline, spinning variation after variation. This highly constrained formula is hypnotic, transcendent, and somehow narrative in that way that variations can be when done perfectly. A melancholy sunset, brushed in slow and red over a northern sky. Meaning without meaning, a world within a dewdrop, minor key scales without end.

The killer performance, with Franzjosef Maier on violin, is no longer so easy to get. It was released in 1990 on CD by Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, and Amazon says it’s out of stock but available new or used starting at $202.02. Ah, connoisseurship is alive and well..

Next:

Keith Jarrett’s Elegy for violin and string orchestra. He wrote this in memory of his Hungarian grandmother, and at its melodic core it lilts that gap-toothed gypsy note, as distinctive as the blue note, recalling the shadowy alleyways of Eastern Europe. As classical motive music some critics find fault with Jarrett’s composition, calling it vague, aimless or even incompetent, which utterly misses the point. Like Michael Chabon, he brings a powerfully asserted and defiant point of view to his art, an insistence on the sensual irrespective of art fashion, a sensitivity to the idiomatic. Jarrett is a knight, a defender of what matters. He has described his pieces as “prayers that beauty may remain perceptible”. In the Elegy, to fail to perceive the beauty is to have an ear unusably distorted by affectation or style. The violin, whether grounded in the dark chords of the orchestra or soaring free from them, transports the listener. The theme is lost in a harmonic labyrinth, the traveler meditative on a path of uncertain return, the dusk now turning to night. But what is given trustingly is returned freely. In the loose reaches of this sound-poem, sound is re-invested with luminance.

Finally:

Spiegel Im Spiegel, by Arvo Pärt. This ten minute work, spare and minimal, occupies an opposite corner to Bach. A piano repeats quarter-note triads, one-two-three, four-five-six, throughout the piece in the middle register, with a stripped-down bass chord occasionally thrumming underneath for a whole beat, a high bell-like note struck at times. The violin, very human in its voice, plays slow fragments of diatonic scales over this ground. (Spiegel Im Spiegel can also be played with a cello, but I think the greater tonal separation of the violin from the piano makes that version more potent.) This music came at the end of Pärt’s self-imposed silence of several years, a period Paul Hillier described as one of “complete despair in which the composition of music appeared to be the most futile of gestures”. Another warrior, then, another defender of beauty. As a rebirth, shorn of the superfluous and reduced to its inmost core, Pärt’s new tintinnabuli style could not be more perfect, and I think Spiegel Im Spiegel— named after mutually reflecting mirrors, evoking infinite regress— is the most devastating expression of that style in its directness and tenderness.

Spiegel Im Spiegel, by Arvo Pärt. This ten minute work, spare and minimal, occupies an opposite corner to Bach. A piano repeats quarter-note triads, one-two-three, four-five-six, throughout the piece in the middle register, with a stripped-down bass chord occasionally thrumming underneath for a whole beat, a high bell-like note struck at times. The violin, very human in its voice, plays slow fragments of diatonic scales over this ground. (Spiegel Im Spiegel can also be played with a cello, but I think the greater tonal separation of the violin from the piano makes that version more potent.) This music came at the end of Pärt’s self-imposed silence of several years, a period Paul Hillier described as one of “complete despair in which the composition of music appeared to be the most futile of gestures”. Another warrior, then, another defender of beauty. As a rebirth, shorn of the superfluous and reduced to its inmost core, Pärt’s new tintinnabuli style could not be more perfect, and I think Spiegel Im Spiegel— named after mutually reflecting mirrors, evoking infinite regress— is the most devastating expression of that style in its directness and tenderness.

5 Responses to violin