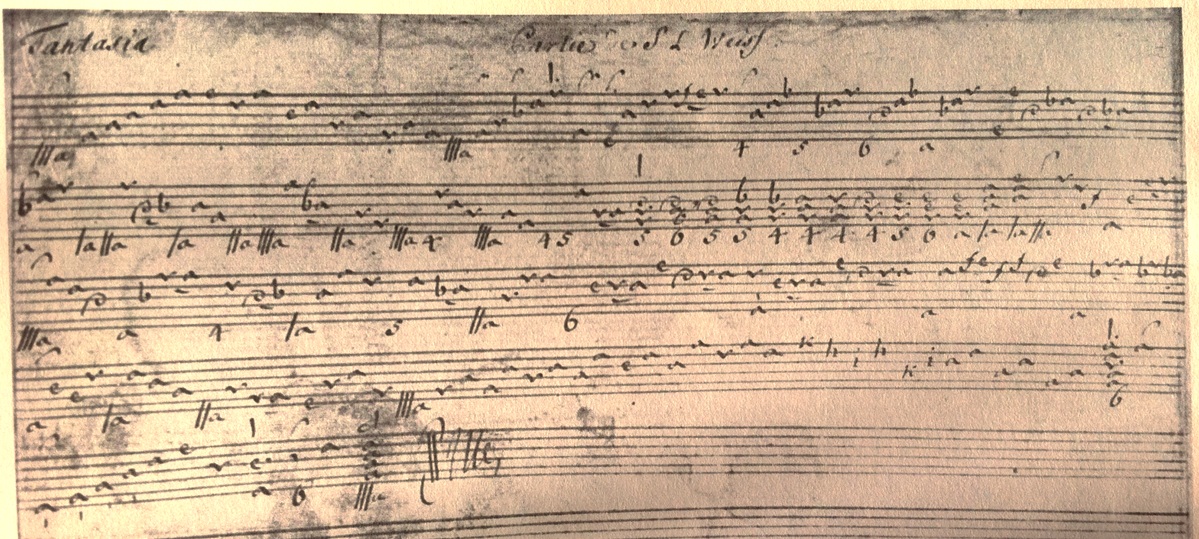

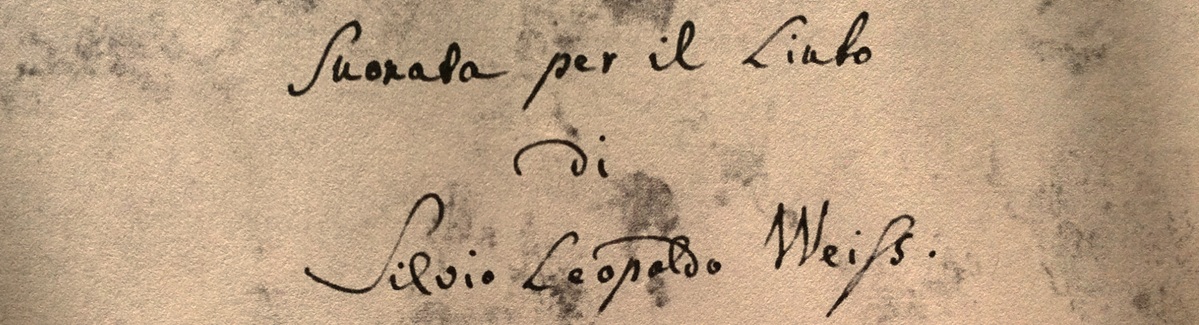

One of my favorite unbarred preludes for baroque lute, by Sylvius Leopold Weiss:

This particular one in d minor—actually it styles itself a fantasia— is so idiomatic and easy to play, it just rolls out from under the fingers, and it’s darkly beautiful.

Unsubstantiated historical speculation follows.

About preludes and their kin: I love these opening pieces to dance suites, which seem to me (and this may be playing fast and loose with the reality of the matter) to have evolved by an organic process from the notes at the beginning of the suite showing the tuning by unisons or octaves.

That’s why these pieces always seem to begin with a casual arpeggio, a preliminary survey of the key, perhaps something you can use to tune the instrument, perhaps something you begin to play and can continue, without a clear transition, from tuning to trying, testing, playing. Hence toccata or the older terms ricercar and the Spanish tiento, touch, exploration, experiment, prelude. Often they develop from these tentative forays into fugal passages, thus further “testing” not only the harmonic character of the key, but the melodic and contrapuntal possibilities of the themes to be developed throughout the suite.

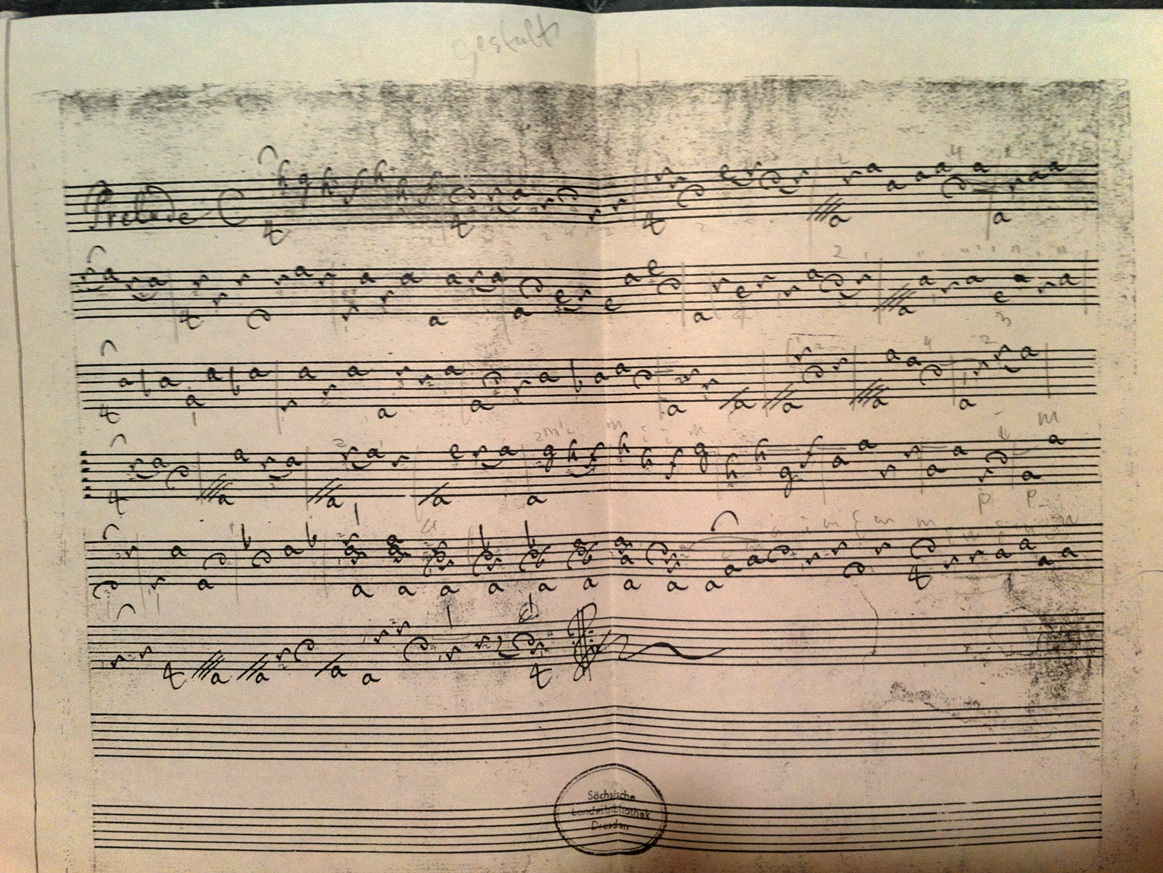

Typically a Weiss prelude breaks down into block chords at a certain point, in the case of this fantasia in the second half of the second line. (I can’t find a copy, but seem to remember that Bach does this somewhere in the suites for solo cello also.) Modern players tend to just arpeggiate the chords, following the implied pattern in the rest of the piece, but I’m fairly convinced that Weiss intended these passages to be improvised over the chordal structure, sort of like a jazz solo. I imagine literal enunciation of the chords as written to have been a stopgap for beginners. It still sounds beautiful that way.

Unbarred: meaning, unlike the rhythmic dances that follow (e.g. allemande, minuet, sarabande, gigue) there are no barlines, no explicit beat. It’s suggestive of a looseness in the rhythm, an interpretive freedom consistent with the exploratory nature of the piece. My old teacher, Pat O’Brien, penciled in the word gestalt over the top of one of these. I don’t remember the context, but I imagine he meant that to play these pieces one can’t be too literal, one must be able to flow from position to position without being too tightly bound to the notes, to allow the rhythm to emerge variably from the music instead of constraining the music to follow the rhythm, as one will when one gets down to business in the allemande.

In the end I think it’s this sense of gestalt that makes me love these openings even more than the suites that follow.

“I like the indefinite, the boundless; I like continual uncertainty.”

—Gerhard Richter