“Sorel’s basic character flaws had all cemented by the age of fifteen, a fact which further elicited my sympathy. To have all the building blocks of your life in place by that age was, by any standard, a tragedy. It was as good as sealing yourself into a dungeon. Walled in, with nowhere to go but your own doom.”

—Haruki Murakami, Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.

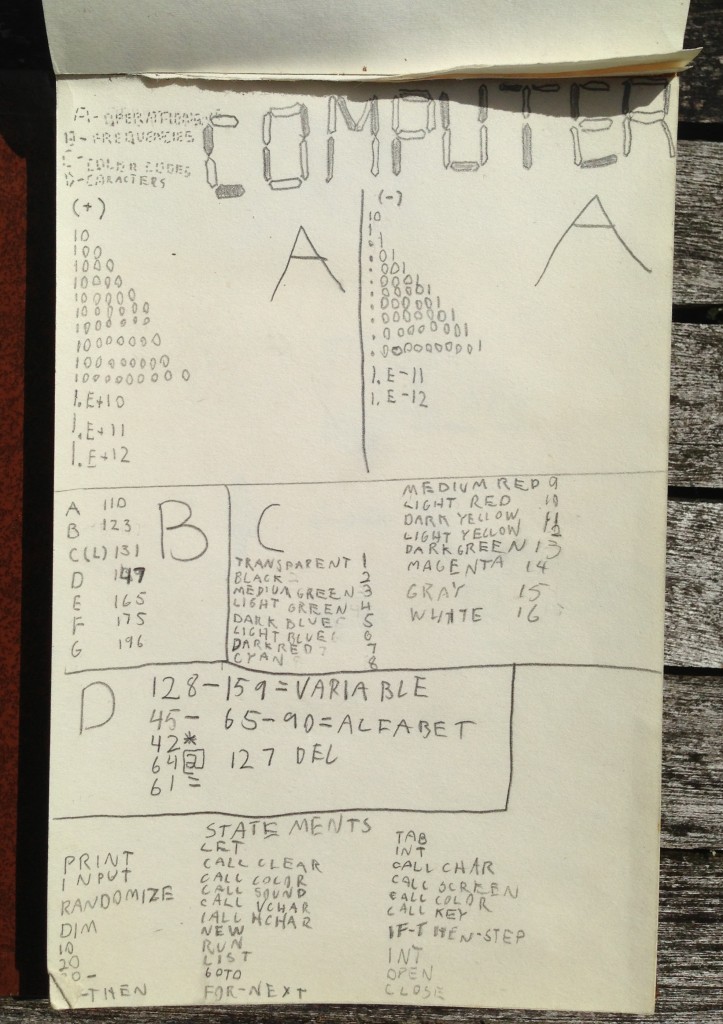

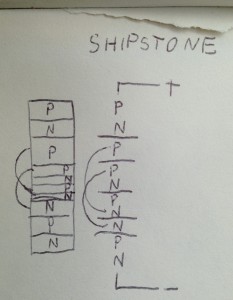

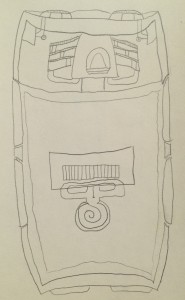

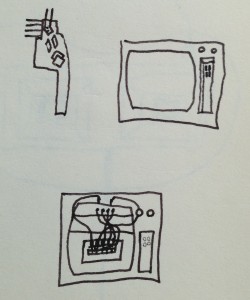

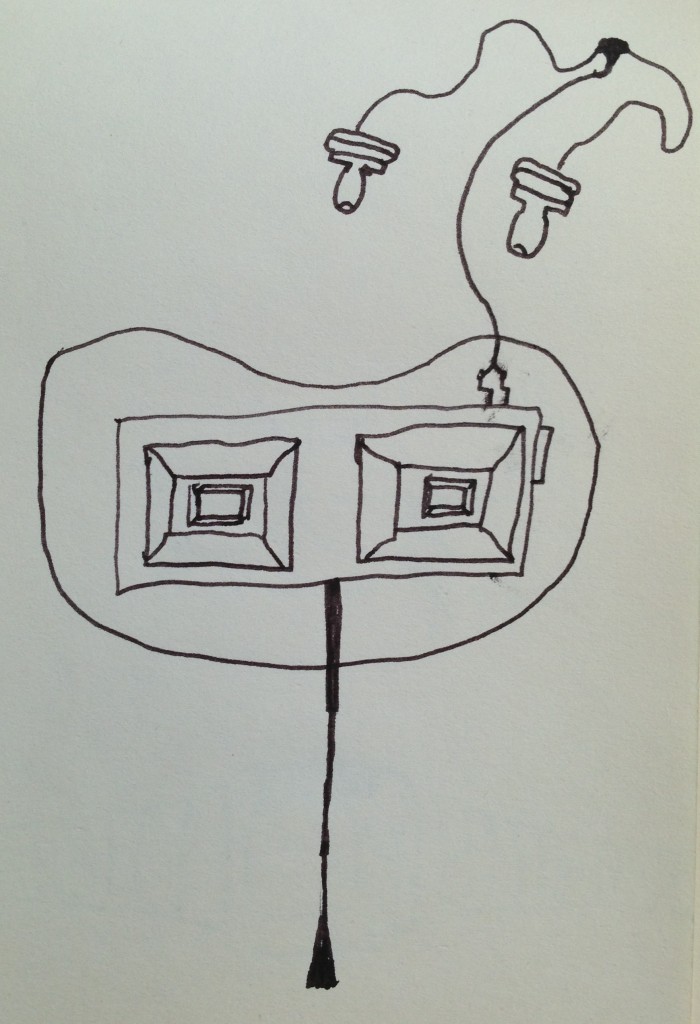

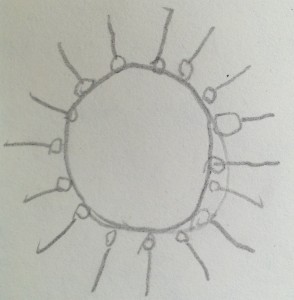

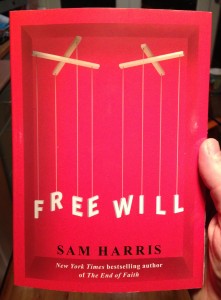

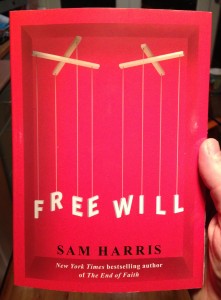

Somewhere on the bramble-choked planet where philosophers live, Sam Harris wrote a little 66-page book called Free Will. Harris is a fine writer and to the point; also, his minimal title consists of the perfect number of characters to hang from a pair of puppeteer’s operating crosses. As this image suggests, he is a hard core determinist: (a) the brain obeys the laws of physics, and (b) there is no “mind” that isn’t a function of the physical processes of the brain, therefore, (c) the idea of free will doesn’t even make sense conceptually:

Somewhere on the bramble-choked planet where philosophers live, Sam Harris wrote a little 66-page book called Free Will. Harris is a fine writer and to the point; also, his minimal title consists of the perfect number of characters to hang from a pair of puppeteer’s operating crosses. As this image suggests, he is a hard core determinist: (a) the brain obeys the laws of physics, and (b) there is no “mind” that isn’t a function of the physical processes of the brain, therefore, (c) the idea of free will doesn’t even make sense conceptually:

“The illusion of free will is itself an illusion.”

For those of us who are not dualists (that would be everyone “philosophically respectable”, as Harris puts it), (a) and (b) are givens.* Harris concedes that there is an (also respectable) spectrum of thought called “compatibilism” that attempts to reconcile (a) and (b) with some meaningful definition of free will; many thinkers of this school (like Daniel Dennett) use definitions based on “freedom of action”.

But Sam Harris is not a compatibilist: this book is an extended case against them. I agree with many of his arguments. To boil it down, in order to work within the standard true/false logical constructs of modern philosophy and still leave room for free will, one is forced to define it in a more or less legalistic sense, as in “of one’s own free will, not coerced at gunpoint”. This “freedom to act in accordance with one’s desires” is a nice thing to have, and it might be relevant in court, but I agree with Harris that it’s irrelevant to the questions about free will that seem problematic or interesting in light of determinism. What’s interesting about free will is the idea of agency itself, of having autonomous desires and motivations in the first place— whether they’re carried out or thwarted. But how could there be a “could”, or a “should”, or a “could have”, or a “should have”, if the future— including every choice you make— is predetermined?

*There are some asterisks. Quantum physics has sometimes been invoked to try to rescue the situation, but this is silly— not because quantum effects don’t matter, since ultimately, at least over long enough timescales, they must— but rather because being at the mercy of coin flipping instead of billiards doesn’t somehow open a whitespace for freedom of will or action. It just introduces a noise source. To place the locus of our agency on a random variable is about as meaningful as claiming that a thermostat is conscious. (Oh wait, that’s been done too.) Anyway we have reasonable evidence that our moment-to-moment decisions and actions rely on neurophysical processes that don’t operate near the quantum scale. If we were to somehow prepare an ensemble of identical copies of a person and do a moral or psychological experiment on the cohort under identical experimental conditions, we’d be very unlikely to get any variability in the result. It therefore seems to follow that there is no “freedom” in such a behavioral choice, any more than we can say a rock has “freedom” with respect to whether or not to fall if dropped.

Before unpicking his argument, let me state for the record that I think I really like this Sam Harris person. He takes a hard line about being nonreligious in a way that few decent-minded people will admit to in public these days— at least in the US, given a discourse that has polarized around, on one hand, the hard nuggets of mutually exclusive religious views, and on the other hand, a diffuse well-meaning liberalism within which we must pretend to be nonjudgmental. Obviously if forced to choose camps I’ll gladly live in the latter and wear a forced smile, but Harris is refreshing when he

“[…] advocates a benign, noncoercive, corrective form of intolerance, distinguishing it from historic religious persecution. He promotes a conversational intolerance, in which personal convictions are scaled against evidence, and where intellectual honesty is demanded equally in religious views and non-religious views. He suggests that, just as a person declaring a belief that Elvis is still alive would immediately make his every statement suspect in the eyes of those he was conversing with, asserting a similarly non-evidentiary point on a religious doctrine ought to be met with similar disrespect. He also believes there is a need to counter inhibitions that prevent the open critique of religious ideas, beliefs, and practices under the auspices of “tolerance”.”

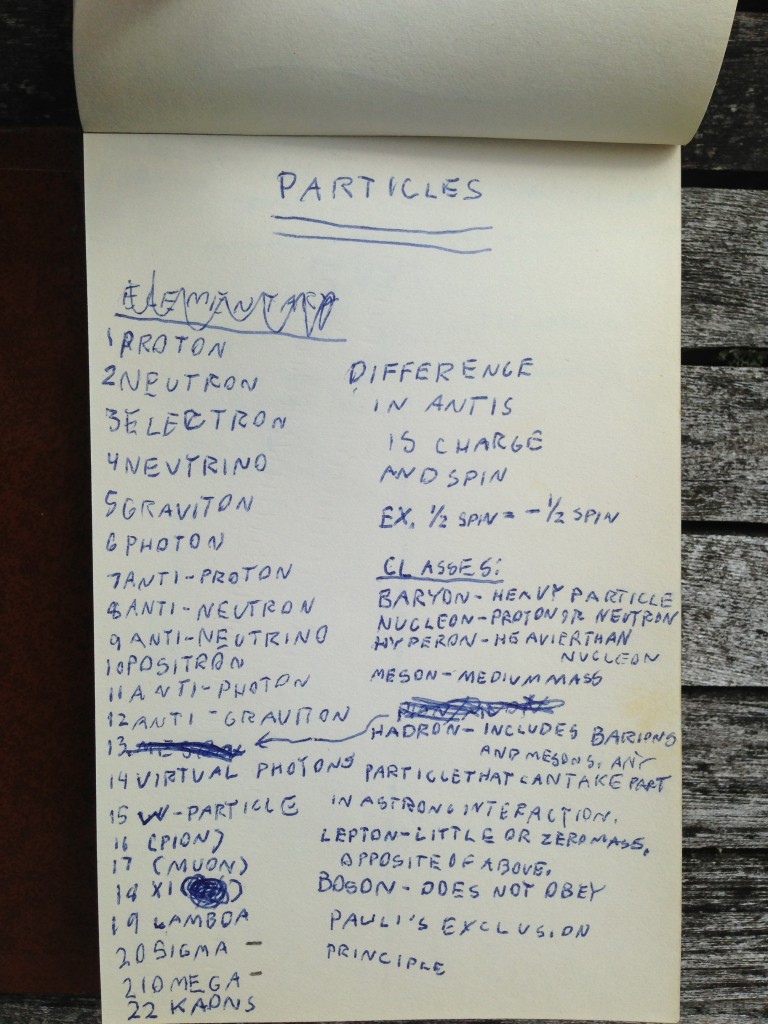

Yay! OK, but the gospel is not all good. The overarching problem with Harris is that in his merciless reduction to the evidentiary, he leaves no space for a lot of useful ideas. First among these is the idea of paths not taken in our behavior— of possibility. In attacking this, he invokes classic fMRI and masking experiments that reveal how tenuous the relationship can be between our awareness and our brain processes. In the masking experiments, stimuli can be delivered and then “cancelled out” by a second stimulus, although the unconscious brain can be left in a “primed” state. There are also decisionmaking experiments, old and new, in which populations of neurons in the brain appear to “know” what you’re going to decide before “you” do. These experiments are certainly intriguing and violate our intuitions about causality and agency— if we think like philosophers or legal theorists, and insist that agency can only be somehow located in the “text” of our conscious narrative. If we think more like neuroscientists instead, we realize that whatever this special stuff is that we call awareness, attention, or consciousness, it’s supported by a lot of neural machinery, and this machinery doesn’t operate instantaneously or above board. Of course we can’t be “aware” of every aspect of its operation— that we are aware at all is the miracle. Lots of corners are cut— thankfully— in our self-awareness.

The miracle of self-awareness seems to be a product of our ability to model relevant aspects of the world around us, and people around us. (And since the self is a person too, it should be unsurprising that we can experience the special elliptical thrill of modeling ourselves.) It’s not hard to see why these would be useful faculties. A good argument can be made that the whole point of a brain is to predict the future, and especially the futures of others and of ourselves, perhaps under hypothetical circumstances. In a troupe of apes, the ability to empathize— to understand what that other ape is about to do, and why— allows one to behave in ways that further one’s own goals, or the goals of the community. Brains are good at predicting the behaviors of brains, and they do it by forming models. When we try to formalize such models, and maybe even test them with experiment, we call the result “psychology”. It may not be particle physics, but it sure is useful.

In support of his belief that the mind is nothing but a puppet or helpless witness to unknowable physical processes, Harris claims, rather fatuously, that our behavior is all mysterious:

“For instance, in my teens and early twenties I was a devoted student of the martial arts. I practiced incessantly and taught classes in college. Recently, I began training again, after a hiatus of more than 20 years. Both the cessation and the renewal of my interest in martial arts seem to be pure expressions of the freedom that Nahmias attributes to me. I have been under no “unreasonable external or internal pressure.” I have done exactly what I wanted to do. I wanted to stop training, and I stopped. I wanted to start again, and now I train several times a week. All this has been associated with conscious thought and acts of apparent self-control.

However, when I look for the psychological cause of my behavior, I find it utterly mysterious. Why did I stop training 20 years ago? Well, certain things just became more important to me. But why did they become more important to me— and why precisely then and to that degree? And why did my interest in martial arts suddenly reemerge after decades of hibernation?” (p. 42)

This is the strange corner Harris finds himself backed into by his insistence on an all-eclipsing determinism. Because if everything is determined, then how could anything have a “why”— since a “why” implies a “why not”, and determinism implies that there cannot be a not.

“You will do whatever it is you do, and it is meaningless to assert that you could have done otherwise.” (p. 44)

Moreover, determinism stipulates exactitude, which for him, owing to a conflation between levels of description, means that no approximate or probabilistic concept can enter into the discourse. Finally, by not acknowledging the difference in level of description between physics and psychology, Harris seems to invalidate the very idea of a satisfactory “why” under any circumstance by insisting that it be supported by— what?— maybe an infinite regress of satisfactory and precise “whys” underneath it, going back to the Big Bang?

Thankfully Harris does not actually suffer from the narrative deficit he claims; he goes right on to answer his own unanswerable question, reassuring us that he’s not actually that dense, before beating a hasty retreat:

“I can consciously weigh the effects of certain influences— for instance, I recently read Rory Miller’s excellent book Meditations on Violence. But why did I read this book? I have no idea. And why did I find it compelling? [...] Of course, I could tell a story about why I’m doing what I’m doing— which would amount to my telling you why I think such training is a good idea, why I enjoy it, etc.— but the actual explanation for my behavior is hidden from me. And it is perfectly obvious that I, as the conscious witness of my experience, am not the deep cause of it.” (p. 43)

Ultimate or “deep” causes aren’t necessarily so relevant. Whys themselves have a why, which is to model. And we are model-makers to a fault. We can easily be tricked into revealing how often we can make false assumptions or rationalize our own behavior, making up stories that can bear little relation to the empirical “truth”. But often, that story-making capability is powerful and predictive. We use it constantly— in every conversation, every considered decision.

Let’s take an example. A gifted analyst and storyteller like Dan Savage can read a short letter from one of his fans, or listen to a quick phone message, and by drawing on his “training set”— that is, his empathy and the pattern matching afforded by hundreds of thousands of such interactions over the years— he can rapidly form insights that have materially helped many people: he is a master of the “why” in his domain. Consider this recent post, chosen more or less at random:

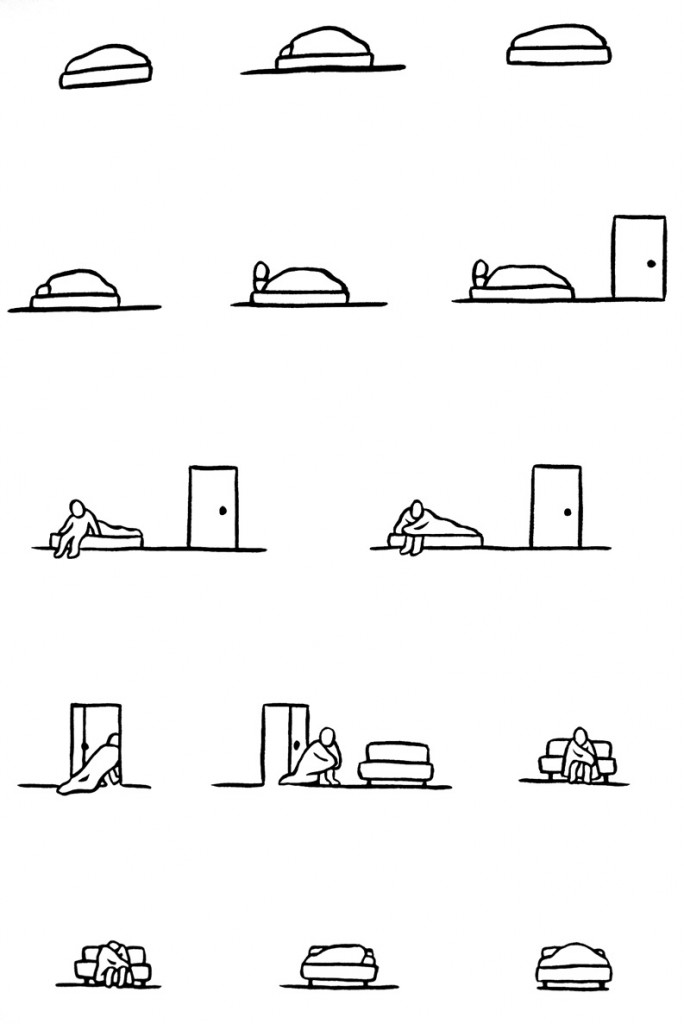

I’m 19 and closeted. I’ve been chatting with a guy on the Internet for six months and now he wants to meet. I’m convinced that he’s too good for me. Aside from looks, he’s out and older and I don’t know why he’d want to be with someone like me. My other online friends— they’re the only people I’m out to— think we should meet. I’m effing scared. I’m not going to ask you to compare our pics, but is there a concrete checklist to verify if someone is out of your league? –Insecure In Internetland

Response:

The good news: If you meet this boy and he’s into you, III, then you’re in his league. That’s because each and every one of us gets to decide who plays in our own personal league. If he invites you to play, you’re in.

Now the bad news: There’s lots of scum floating around on the Internet [...] and you have to be careful. While this may simply be a case of your own insecurities preventing you from recognizing whatever it is about you that this other guy finds attractive, something more sinister could be going on. You say you don’t know why someone better looking, older, and more experienced would want to meet you. Unfortunately in some cases it’s because younger, closeted, and insecure guys are easier to manipulate. So this guy is either honestly into you or he’s an asshole looking to take advantage of your youth and inexperience. If you decide to meet him, III, meet in a public place, tell someone where you’re going, and watch out for red flags. Does he pressure you? Does he try to get you to do things, sexual or otherwise, that make you uncomfortable? If so, run like effing hell.

There’s much to take in here. Dan recognizes salient elements in the situation from sparse data. He pattern matches. He turns a set of priors into a predictive narrative. He explores more than one storyline. He considers the roles of possibly unreliable narrators— both III and his Internet crush. He articulates important uncertainties (while neglecting unimportant ones) and frames behavioral tests designed to resolve them. He considers motive, models best and worst outcomes for every party, aligns his own interests relative to these, and suggests specific actions appropriate to optimizing for the desired outcome while controlling for risk. Whew! Let me know when an AI can do all of that! When the robots put Dan out of a job, humanity will have ceased to be relevant.

All of this is implicit in what I suppose we call “wisdom”.

So how does Dan do it? We don’t quite know the details, of course, but there’s a good deal we can posit.

Dan deals in information. His model is necessarily much simpler than everything it models. He’s not running physical simulations in his head of all of the molecules in someone else’s brain, hoping to be able to run the code faster than reality on his poor slow wetware. He’s clustering, condensing, simplifying, using narrative and metaphor, reasoning, telling himself stories, using his gut, associating, annealing, remembering, generalizing, mirroring, and so on. By using these tricks he— we— can extract meaning from raw experience over multiple timescales, and use the meaning to inform our behavior.

Because meaning is inherently a simplification, it necessarily admits a thickness of possibility. When we say “chair” we’re not specifying all of the particles in the chair. Practically speaking, that would be both impossible and pointless, because in that overly specific description we’d have no concept of chair, and we couldn’t generalize or reason about chairs— in fact we could never even recognize another one. So do chairs have a basis in physics? Yes and no. There’s no chair-soul; every instance of a chair is indeed made out of nothing but particles, and its behavior is entirely determined by the particles’ behavior. On the other hand the idea of a chair is something quite abstract, and quite useful. To call it “not real” would be silly. Yet its reality depends on a different level of description— the level of talking and thinking and reasoning, not solving for wavefunctions.

Also, this kind of thick reality has inherent fuzziness and subjectivity. Perspective matters. A question like “is this a chair?” could be legitimately answered not only with a “yes” or a “no”, but also “maybe”, “it sure is a funny one”, or “it’s a dollhouse chair, so the answer depends on why you’re asking”.

(This is why formal logic is so easily abused at the level of description where we live most of the time. It seems that philosophers tend— perhaps willfully— to pretend to live elsewhere. Maybe on their planet counterfactuals like “if I knew the positions and momenta of all of the particles in your brain” somehow make sense, while other counterfactuals like “if I had decided to make it to the gym today” or “if I were you” don’t. Normally I’d be all into space travel, but no need to send me the brochure for this planet.)

Causes, as we understand them, are like chairs. “Person”, “mind”, and “motive” are like chairs. Morality, empathy and agency are like chairs. They aren’t supernatural, they’re very much grounded in the physical world, but they are concepts, and as such they have their own coarse-grained reality. Useful concepts and categories have probability and uncertainty quite distinct from the much more literal statistical or quantum uncertainties of the physical world. Without the uncertainty, the blurring, concepts could not be applied, generalized or operated with. The uncertainty is inherent. If one is skilled at the art of consciousness like Dan Savage, one can both exploit and model that uncertainty, weaving intention, agency, prediction, empathy and possibility into that wonderfully dense sparseness that defines what it means to be a mindful person.

“Is the mind beyond you?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “There are times when the understanding does not come until later, when it no longer matters. Other times I do what I must do, not knowing my own mind, and I am led astray.”

“How can the mind be so imperfect?” she says with a smile.

I look at my hands. Bathed in the moonlight, they seem like statues, proportioned to no purpose.

“It may well be imperfect,” I say, “but it leaves traces. And we can follow those traces, like footsteps in the snow.”

“Where do they lead?”

“To oneself,” I answer. “That’s what the mind is. Without the mind, nothing leads anywhere.”

I look up. The winter moon is brilliant, over the Town, above the Wall.

“Not one thing is your fault,” I comfort her.

—Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World