Maybe it’s the recent demise of the great Captain Beefheart, which is a reminder of the way music, 30 years ago still a medium for revolution, no longer has a past or a future, but has congealed into a timelessly suspended orchestral chord like the final twenty bars of a dirge by Arvo Pärt. Maybe it’s all the delta blues I’ve been listening to, and that time last week I fell asleep in my chair to Strauss’s last songs, the liquid voice of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf floating angel-like over a German meadow at dusk. Or the solo passages from Keith Jarrett’s Elegy for Violin and Strings, sunlight pooling in a dark forest, during which, while tearfully slicing shallots for a stew, I nearly took off the last joints of the middle and index fingers of my left hand.

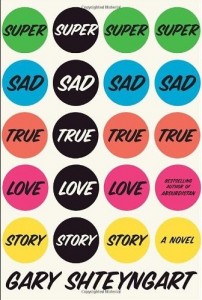

More likely, it’s the brutal new book by Gary Shteyngart, Super Sad True Love Story, that has me thinking about death.

More likely, it’s the brutal new book by Gary Shteyngart, Super Sad True Love Story, that has me thinking about death.

It’s unexpected. His last book, Absurdistan, was sophomoric satire. It earned plenty of critical praise, but didn’t do it for me. Super Sad is of an entirely different order. The writing is beautiful. The story is powerful. The characters run true, in a way that suggests the agonies of autobiography. In theory, I suppose Super Sad is science fiction, in that it takes place in a near future and certain elements hinge on technologies that are not yet (quite) real.

The names alone. Soylent Green. Logan’s Run. Here were Joshie’s beginnings. A dystopian upper-class childhood in several elite American suburbs. Total immersion in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. The twelve-year-old’s first cognition of mortality, for the true subject of science fiction is death, not life. It will all end. The totality of it. The self-love. Not wanting to die. Wanting to live, but not sure why. Looking up at the nighttime sky, at the black eternity of outer space, amazed. Hating the parents. Wanting their love. Already an anxious sense of time passing, the staggered bathroom howls of grief for a deceased Pomeranian, young Joshie’s stalwart and only best friend, felled by doggie cancer on a Chevy Chase lawn. [p.217]

The gorgeous sentences were a surprise. Our friend Blaine, who recommended the book to me, floated the theory that perhaps Shteyngart had finally come into his inheritance as a writer in English, that perhaps, like Nabokov— another St. Petersburg native— he’s an émigré both in body and language. The back flap seems to refute this idea, claiming that the Shteyngart family moved to the US when he was only seven years old. But then, I wasn’t so much older when my family moved here, and I still don’t feel assimilated. And yes,

Shteyngart spent the first seven years of his childhood living in a square dominated by a huge statue of Vladimir Lenin in what is now St. Petersburg, Russia; the city was then known as Leningrad. He comes from a Jewish family and describes his family as typically Soviet. His father worked as an engineer in a LOMO camera factory; his mother was a pianist. Shteyngart emigrated to the United States in 1979 and was brought up with no television in the apartment in which he lived, and no spoken English. He did not shed his thick Russian accent until the age of 14.

Aside from the obsession with death of Lenny Abramovitz, the 39 year old nebbish in the center of this book’s nihilistic vortex (and stand-in for the 38 year old Shteyngart), other themes of Super Sad include the death of childhood, the death of relationships, the death of words, the death of books, the death of the Web, the death of New York, the death of the USA, and the death of the human species. This isn’t a good book to read in a hospital room, or during exams, grant proposals, breakups, elections, or midlife crises.

As a Jew and a Russian émigré, perhaps Shteyngart comes well equipped to understand death in a truer and fundamentally un-American way, as a real presence and absence, as the negative space around, before and after anything of value.

Childhood

The joint returned, passed by a slender, unfamiliar woman’s hand, and I toked harshly from it. I settled into a memory of being maybe fourteen and passing by one of those then newly built NYU dormitories on First or Second Avenue, those multi-colored blobs with some kind of chicken-wing-type modernity pointedly hanging off the roof, and there were these smartly dressed girls just being young out by the building’s lobby, and they smiled in tandem as I passed— not in jest, but because I was a normal-looking guy and it was a brilliant summer day, and we were all alive. I remember how happy I was (I decided to attend NYU on the spot), but how, after I had walked half a block away, I realized they were going to die and I was going to die and that the final result— nonexistence, erasure, none of this mattering in the “longest” of runs— would never appease me, never allow me to enjoy fully the happiness of the friends I suspected I would one day acquire, friends like these people in front of me, celebrating an upcoming birth, laughing and drinking, passing into a new generation with their connectivity and decency intact, even as each year brought closer the unthinkable, those waking hours that began at nine post meridian and ended at three in the morning, those pulsing, mosquito-bitten hours of dread. [p.237]

In Mexico, Dia de los Muertos celebrates death just as the American Halloween jokily skirts it. The sickly sweet candies both preserve against corruption and evoke it, the sweetish odor of decay familiar to anyone still living in connection with the underlying realities of the farm, the deathbed, the slaughterhouse.

Relationships

The love story of Lenny Abramov and the much younger Eunice Park is indeed super sad. True to its title, not a single relationship introduced or consummated in the book outlives its 331 pages. Of course, to put a cheerful spin on things, we can quote Dan Savage: “every relationship fails... until one doesn’t”. This claim is problematic in several ways, the most interesting of which is that it presumes that the measure of a relationship’s “success” is the death of one or both of the parties involved.

Words

A co-op woman, old, tired, Jewish, fake drops of jade spread across the little sacks of her bosom, looked up at the pending wind and said one word: “Blustery.” Just one word, a word meaning no more than “a period of time characterized by strong winds,” but it caught me unaware, it reminded me of how language was once used, its precision and simplicity, its capacity for recall. Not cold, not chilly, blustery. A hundred other blustery days appeared before me, my young mother in a faux-fur coat standing before our Chevrolet Malibu Classic, her hands protectively over my ears because my defective ski hat couldn’t be pulled down to cover them, while my father cursed and fumbled with his car keys. The streams of her worried breath against my face, the excitement of feeling both cold and protected, exposed to the elements and loved at the same time.

“It is blustery, ma’am,” I said to the old co-op woman. “I can feel it in my bones.” And she smiled at me with whatever facial muscles she still had in reserve. We were communicating with words. [p.305]

Books

[Milan] Kundera forced me to ponder my mortality some more.

Eunice’s gaze had weakened, and the light had gone out of her eyes, those twin black orbs usually charged with an irrepressible mandate of anger and desire.

“Are you following all this?” I said. “Maybe we should stop.”

“I’m listening,” she half-whispered.

“But are you understanding?” I said.

“I’ve never really learned how to read texts,” she said. “Just to scan them for info.” [p.277]

Amazon.com’s homepage is claiming that the Kindle is their number one selling, most gifted item ever. And the glow of faces lit from below by iDevices on the bus with me now, perfect monoliths of consumer technology. I’m rowing upriver with these “nonstreaming bound media artifacts” I carry around in my backpack. Shteyngart is essentially right, within a decade, books will look like Amish hats, or perhaps more aptly like the payess of an ultra-orthodox Jew on the L train, suggestive of an underlying unwashed odor. And then deep reading will go too, cf. The Shallows, by Nicholas Carr.

The Web

While books have the stolid survivability of a Galapagos tortoise in a ship’s hold, the Internet technologies that replace them are disembodied, fragile, nothing but a wispy thought or soul reborn and refreshed in every moment of “uptime”. As kids we read about the “candles of knowledge” that the monks kept alight in their millennial monasteries, the libraries of medieval Europe. But our candles are literally that, will be extinguished the moment the lights go out. Or before, since the systems that keep these candles alight are run by companies that have no interest in burning tallow if there are too few consumer-moths fluttering around the flame to monetize. Yesterday Yahoo announced that they’ll be shutting down Delicious,

the Internet’s memory storage device. In the 7+ years of its existence it has recorded the collective online journeys of millions of users during a time when the Web was evolving dramatically. Those memories are irreplaceable and have enormous value both to their owners (the users) and to society.

This blogger suggests scraping the Delicious records before the plug is pulled and donating them to the Library of Congress or the Smithsonian! Thus the recessional of the hard drives back into the monastery.

When the lights go out on New York in Super Sad, Eunice Park’s frantic attempts to communicate with her friends and family are met with the following 404:

GLOBALTEENS AUTOMATIC ERROR MESSAGE 01121111:

We are SO TOTTALY sorry for the inconvenience. We are experiencing connectivity issues in the following location: HERMOSA BEACH, CA, U.S.A. Please be patient and the problem should resolve itself like whenever.

Free GlobalTeens Dating Tip: Don’t ever fold your arms in front of your date. That says you don’t totally agree with what he’s saying or maybe you’re not into his data. Instead put your hands out in front of you, palms open, like you want to be cupping his balls! Get a degree in Body Language, girlfriend, and you’ll be giving head to the class. [p.263]

After a few days of no connectivity, people in Lenny’s apartment building begin to suicide, like cells tuning into the apoptosis signal after the death of the body.

New York

A pink mist hovered over the mostly residential area once known as the Financial District, casting everything in the past tense. A father kept kissing his tiny son’s head over and over with a sad insistence, making those of us with bad parents or no parents feel even more lonely and alone.

We watched the silhouettes of oil tankers, guessing at the warmth of their holds. The city approached. The three bridges connecting Brooklyn and Manhattan, one long necklace of light, gradually differentiated themselves. The Empire State extinguished its crown and tucked itself away behind a lesser building. On the Brooklyn side, the gold-tipped Williamsburg Savings Bank, cornered by the half-built, abandoned glass giants around it, quietly gave us the finger. Only the bankrupt “Freedom” Tower, empty and stern in profile, like an angry man risen and ready to punch, celebrated itself throughout the night.

Every returning New Yorker asks the question: Is this still my city?

I have a ready answer, cloaked in obstinate despair: It is.

And if it’s not, I will love it all the more. I will love it to the point where it becomes mine again. [p.96]

The United States

… I pondered my father’s humiliation. The humiliation of growing up a Jew in the Soviet Union, of cleaning piss-stained bathrooms in the States, of worshipping a country that would collapse as simply and inelegantly as the one he had abandoned. [p.321]

It’s a false analogy to call the US “middle-aged” or “over the hill”, in that such terms are born out of analogy with organisms like us, with telomeric clocks that tell us when it’s time to die after our fourscore-odd years— assuming we’ve made it that far. The collapse of a society seems more like a diffusive capture process, a drunkard’s walk in which every step takes us closer or farther from one or another kind of collapse-scale event. We stumble around in a polyhedron of stability, perhaps take a step back from one brink with the passage of universal healthcare, toward another with every Lyndon LaRouche demonstration.

Across the thresholds, the lawless homicidal madness of Ciudad Juárez, the naked survival-of-the-fittest in the streets of Lagos, the catastrophic breakdowns in social cohesion that happened in Bosnia and in Rwanda, the eco-disasters chronicled in Jared Diamond’s Collapse, the disintegration of the USSR. There may be no clock, but a country, a society, can’t last; it rolls the dice every year. Change is coming, perhaps gentle, perhaps catastrophic, perhaps soon, perhaps not for a while. As the cells in these organisms, what can we hope for? To avoid living in fear and dread, to sleep well at night, and insofar as we can, to try to survive with our “connectivity and decency intact”.

Humans

We were talking, placidly despite the wine intake, about global warming and the end of human life on earth. The Italians were describing our role on the planet as that of bothersome horseflies, and the planet’s self-regulating ecosystems as a kind of gigantic fly-swatter. I could not understand how, as parents, my friends could even begin to imagine the extinguishing of their son’s world… [p.330]

Yes, I find it much easier to accept my own death than the deaths of these larger things.

Pingback: Blaise Aguera y Arcas, music and literary critic | Beyond the Beyond | Wired