I’m going to make a confession, get something off my chest that has gnawed at my conscience for many years (ok, just the occasional pang these days, but still). Electrophysiology was a bit of an obsession for me as a kid, though I didn’t know the word. Certain small mammals were dissected on our dining room table around age 7–9, and the “galvanic experiment”— using batteries to make recently disembodied muscles twitch— was a big thrill. Then I became fixated on doing the opposite— measuring signals electronically from living sensory receptors. But how to do it? There were some attempts, including a rather gruesome one with a garden lizard’s head, all failures.

I’m going to make a confession, get something off my chest that has gnawed at my conscience for many years (ok, just the occasional pang these days, but still). Electrophysiology was a bit of an obsession for me as a kid, though I didn’t know the word. Certain small mammals were dissected on our dining room table around age 7–9, and the “galvanic experiment”— using batteries to make recently disembodied muscles twitch— was a big thrill. Then I became fixated on doing the opposite— measuring signals electronically from living sensory receptors. But how to do it? There were some attempts, including a rather gruesome one with a garden lizard’s head, all failures.

One evening, I overheard an adult saying something sage about the extraordinary sensitivity of cat whiskers, how they can “see” in the dark with them. (It turns out this is true for rats, but not for cats, whose whiskers are about as useful as ours.) I imagined some kind of mysterious action at a distance, an electrostatic effect maybe, and slyly shifted my gaze under the table, where our very sweet Siamese was curled into a ball of unsuspecting monochrome fur, napping. I picked him up, took him into my bedroom, closed the door, snipped off a whisker, then began poking at it with alligator clips, trying to get a signal on my multimeter as I waved it around the room. Nothing. Perhaps whiskers only respond to conductors, or only at very close range? Still nothing. Of course, because I needed to instrument the bulb at the root of the whisker, where the nerves would be! It would have to be carefully pulled out then, not just cut.

Until this point, the cat had been following my antics with only mild concern, but the whisker-pulling was going too far. Was I an autistic child, unable to empathize with my desperately struggling pet, who also happened to be my favorite and most loyal companion? I wish I could say that I was, but I think not. I knew this would hurt. It hurts to pull out hair, and a whisker is a lot thicker and more deeply bedded. But in my excitement to measure an electrical response I felt that the cat’s objections took a backseat to the higher aims of our project. We were collaborators, he and I, and knowledge carries a price. One of my earlier attempts had involved cutting off a little flap of skin from my own knee and trying to record touch, hot and cold sensations from it (unsuccessful, but could be passed off later as an accidentally skinned knee). Now that I think about it, it’s curious, the way I don’t remember feeling any pain from the knee experiment at the time, fixated as I was on the outcome. Sort of like not laughing when you tickle yourself.

It’s a pity, adages notwithstanding, that the cat didn’t share my curiosity and its anesthetic qualities. Because now I need to relate the most damning part of the story. I was persistent. I thought I might need to vary my recording technique. I thought some whiskers might be much more sensitive than others. I thought perhaps a whisker’s magic properties didn’t survive long in the open air. In short, I believed in trying again. And dear reader, I did. I tried until there were no whiskers left.

The cat forgave me eventually. Whiskerton was a heartbreakingly forgiving animal.

* * *

Fifteen years later, Adrienne and I were doing pretty much the same thing in Bill Bialek’s lab, sticking electrodes into fly brains and recording neural spikes. That was a beautiful and classic experiment. The fly was immobilized in a blob of wax, watching an oscilloscope screen with moving bar patterns, with a little cup under its proboscis full of sugar water to keep it alive. Think “A Clockwork Orange”. The electrode was in one of the large stereotyped neurons common to all flies, H1, which encodes wide-field horizontal motion. It’s diode-like, emitting a flurry of spikes when the world moves in one direction, remaining silent when it moves in the other. There’s a “left” and “right” H1. You could tell when you had the right neuron by plugging the electrode amplifier into a speaker and listening for the clicks. Wave your hand in front of the fly in one direction, and it sounded like a Geiger counter over Chernobyl milk. In the other direction, nothing.

The flies lived about as long plugged into this apparatus as they would have in the wild. You could record from them day after day. Adrienne and her labmates for some reason thought it compassionate to go into the lab and dropper some more sugar water into the cup on Friday night, even if the fly was unlikely to make it through the weekend. It’s curious, how an animal one wouldn’t think twice about swatting into a Rorschach blot becomes an object of empathy when one has spent an hour embalming it in candle wax and carefully poking a wire into its brain.

* * *

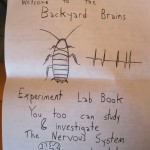

Anselm and Eliot are sweeter children than I was, for sure. Anselm was intrigued but a bit hesitant about the Backyard Brains kit he got for Christmas. Yes, a pair of rogue neuroscientists have done it— they’ve made an inexpensive mail-order amplifier so that kids can record neural spikes at home. No, this isn’t a New Yorker cartoon. You can buy it assembled or just get the raw circuit board and DIY. (Should have done that, Anselm’s almost 9 and I think it’s time for him to learn to solder.) There’s a small speaker built in, or you can hook the amp up to your iPhone and make an oscilloscope. (!) Mail-order cockroaches are extra. The wonderful handwritten manual cheerily notes that the cockroach will be “just fine” after you snip off a leg, and adds that it’s a good idea to dab Vaseline on to prevent it from drying out (the leg first, then the stump).

We didn’t order the cockroaches. Eventually Anselm found a dying beetle outside waving its legs in the air, so this seemed like fair game. I had to do the snipping. With the electrodes in the leg, we were getting quite a bit of noise in the recording, but it looked like there were spikes in there. The chatter seemed to increase when we rubbed the little hairs on the leg. We tried applying current too, and were gratified by a Frankensteinish galvanic muscle twitch. Well, I was very gratified, and Anselm was mostly gratified. His curiosity and his almost eerily intense ethical sense were clearly in conflict. There was a certain ick factor.

Later that evening, we had a long conversation about whether insects have feelings, how they might experience pain, and whether a lingering death on the sidewalk or a quick one at the kitchen table would be preferable, before ranging more broadly into the hinterlands of bioethics.

The five-legged beetle spent its last earthly hours belly to the heavens in our garden.

What is the natural state of a child’s ethics? Is this 19th century question even meaningful without social context? I remember plenty of violence and bullying on the playground, a lot of squashed bugs and frog dissection antics. Anselm and his classmates are a lot more civilized— perhaps at some level more civilized than I am at 35. This seems hopeful with respect to, say, avoidance of future genocides. Then again, are sensitivity and squeamishness the same thing? Is it good to be afraid of worms, or to not know whether a snake’s skin is wet or dry? In Mark Twain’s Mississippi, children traded stiff-limbed dead cats for marbles. They also witnessed lynchings. Roald Dahl thought nothing of putting a dead mouse in his pocket; but he got a thorough caning for the subsequent use of it. Today the kids use a pencil eraser to turn over a dead grasshopper, and spanking is more or less considered child abuse.

Accident or design? The coupling in our heads of the “ick” response, which seems suited mostly for avoiding tainted food, with the empathic shudder, which seems fundamentally about theory of mind and the avoidance of pain in others, seems to me like one of the odder hacks in our evolution. Perhaps it was once a design shortcut, like Volkswagen’s spare-tire-powered windshield washer.

As we civilize ourselves, this curious accident seems to be simultaneously bringing us closer to each other as sentient beings, and further away from the natural world, from the embodied in all its electrophysiological messiness.

Pingback: Tweets that mention backyard brains | style is violence -- Topsy.com