Unlike the red sauce, this post falls in the category of “probably useless”.

Once upon a time I took courses in logic at University. I did fine, because if you know how to do math and program, there isn’t much to it, at least at the undergraduate level. (It was a big disappointment to learn that Gödel’s incompleteness theorems look kind of like St. Anselm’s ontological proof for the existence of god.) I was taken in, I think, by the 19th century idea that logic is somehow the most “fundamental” form of thinking, or the foundation upon which the sciences are built. I’m not sure how this thinking coexisted with my actual work in science, math, etc., where logic almost never came up (except occasionally as a minor element in a proof). No mathematician or scientist I know makes much use of formal logic. If it’s foundational, then this foundation is deeply buried indeed.

It’s true that one can begin with second-order logic, and get from there to numbers and so on. On the other hand, one can begin with numbers, and get from there to logic, a good deal more easily. One can also begin with geometry, or with something very non-reductive, like an animal with a nervous system that can learn associations between correlated complex, noisy sensory inputs. That’s how we do it in real life, after all.

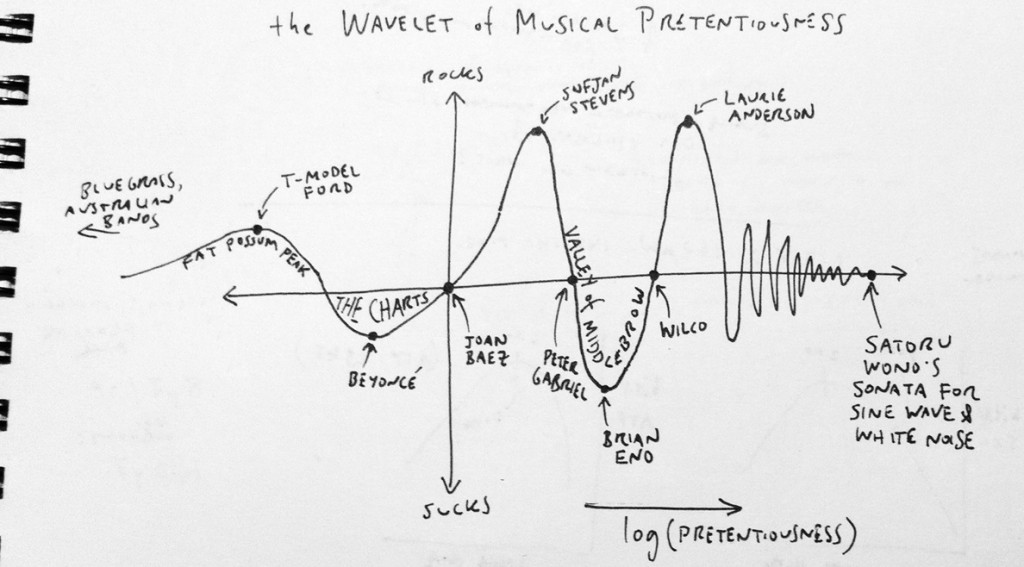

My recent “insight”, if something so trivial could be called that, is that logic not only lacks any special place in the scheme of the universe, but is in fact just a theoretical framework like any other— and a bit of a backwater at that. A theoretical framework is something that hangs together as a system for explaining or predicting phenomena, expressing ideas, generalizing and making inferences, and identifying surprises or violations. To achieve all of that, a framework needs to abstract away, simplify or approximate. Logic relies on some fairly brutal approximations.

In logic, as in pretty much any other framework, the first approximation comes with the assignment of symbols. Many “logic puzzles” play with assumptions regarding the interpretation of predicates, as did Bill Clinton (let’s say generously) when he said “I did not have sex with that woman”. It’s exceedingly easy to get into trouble when one connects the real world, via language and abstraction, with a logical predicate P, or a rule or assertion like P→Q or P&Q. Logic in itself has nothing to say about the validity or correctness of an axiom, meaning a statement used as an input. Worse, such a statement may be correct in the sense originally intended, but may break later on due to shifts in context or externalities. It’s true, for example, that “bike” is short for bicycle; that a bicycle by definition has two wheels; and that an exercise bike has no wheels. “You do the math”, as they say. Luckily for us, our brains don’t go into a kernel panic when we encounter such logical contradictions; in fact, only the most pedantic among us even notice. Not even the pedantic then proceed to conclude that the moon is made of cheese, as clearly it must be:

- B is the set of all bikes

- e is an exercise bike

- W is the set of all things that have two wheels

- C is the set of all things that are made of cheese

- m is the moon

- given:

- e is in B

- (x is in B) implies (x is in W)

- e is not in W

- then:

- from (e is in B) we have (e is in W)

- thus (m is in C) or (e is in W)

- (e is not in W) implies (m is in C)

What’s interesting to notice about this kind of logical nonsense is that one can easily construct examples in which each predicate or rule on its own appears sound, but taken as a whole there’s an inbuilt contradiction. That’s because the context within which each predicate must apply is defined by the domain of the problem, and as one adds more and more predicates, rules and givens, one is often implicitly expanding or redefining the context. Our associations and assumptions about the meanings of symbols in real life are fluid, allowing us to think about all sorts of complex categories, ducking and diving as needed. The price we pay is that we need to keep the big picture in mind, thinking globally in order to ensure that our arguments continue making sense. With logic, on the other hand, we can deal trivially with huge systems and rely on purely local rules to generate cartloads of true statements, as in automated theorem proving; but now we have an exceedingly brittle system— with a single contradiction, the entire structure fails.

But wait, it gets worse. When logic is applied to anything which is not itself a very constrained formal system— such as the world we actually inhabit— then we have uncertainty, so we must at a minimum consider every predicate a random variable. For P&Q we need to write the product of probabilities PQ; for P|Q we need to write P(1‑Q)+Q(1‑P)+PQ = 1-(1‑P)(1‑Q) = P+Q‑PQ; and so on. There’s the somewhat related, somewhat unsatisfying field of “fuzzy logic”, in which we take a continuum of states for what are normally considered Boolean variables, such as “the ball is in the box”. We can always split hairs, and say things like “so where exactly is the ball? Does the box have a lid, and is the lid open? What if the ball is half in and half out?” and so on. One can then assign this variable 0 for fully out of the box, 1 for fully in, and 0.5 when the ball is halfway. This makes my math friends grimace, because now there are all sorts of messy functions to consider, like whether the fuzzy ball-in-the-box measure is by ball volume fraction in the box volume, or by Euclidean distance, or (more usually) by some cooked-up sigmoid with a reasonable lengthscale. Yuck! Now add probability on top of that. What about ensembles of systems, and priors on the probabilities? What about external correlations? What about uncertainty on the uncertainty, and so on to nth order? Yes, dear friends, logic isn’t a fundamental thing at all, but rather a very severe, very brittle approximation scheme in which we neglect all of these effects of context, fuzziness and uncertainty, and pretend that there are such things as Booleans, and ignore whether or not they carry meaning. What we’re left with in this sterile Platonic world is a simple and not particularly powerful framework for manipulating Boolean variables. Is this really a sound foundation for life, the universe, or anything?

And why does all this matter? Should we care that our culture has identified analytical thinking, skilled reasoning and intellectual rigor with this particular rather underpowered formal system?

“Nowhere am I so desperately needed as among a shipload of illogical humans.” — Spock

“I am designed to exceed human capacity, both mentally and physically.” — Data

I can think of at least two places where the logic fetish really hurts us. One is in the teaching of science and math in grade schools, where teachers and administrators who aren’t themselves scientists or mathematicians teach that these fields are grounded in formal methods and logical deduction— at best a very partial view, and certainly not one that encourages the creativity, curiosity and thoughtful exploration that underlie these fields.

The other one is law. We set up increasingly elaborate, quasi-logical legal systems ostensibly to ensure that laws are applied uniformly and consistently, mechanistically, without the human judgment we’d call “corruption” or “judicial activism”. In court, we argue about whether or not a particular predicate or axiom applies in a given situation; of course we’re really arguing about what is or isn’t fair or simply desirable to us, but the argument is always at a remove. Money counts, as this sort of sock puppetry requires professionals “skilled in the art”, as they say. Cases can hinge on nuances in the syntax of a rule. Enormous complexity and expense goes into administering and applying the rulebook. It’s safe to assert that no state or national legal “code” actually “compiles”, in the sense of being self-consistent even under careful treatment of the sets and predicates. The rules are, after all, written over the course of centuries, by a parade of lawmakers with differing agendas and predicate contexts that mutate over time. Paradoxically, the more rules, the greater the need for “interpretation”, which in turn compromises the intended leveling effect.

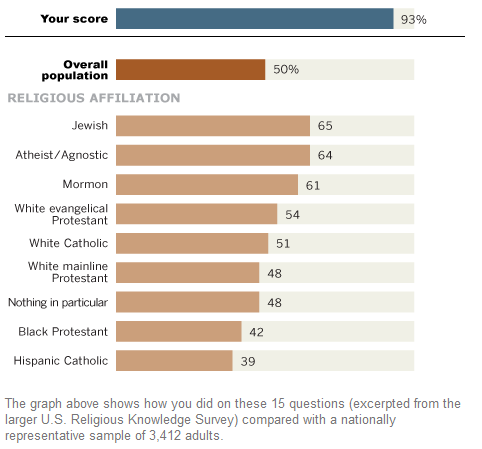

Do we benefit from the extensive legal codebook, presumed fixed at the time of judgment while the “interpretation” is left to those “skilled in the art”? (And does this sound familiar?) Does the resulting mixture of medieval scholasticism, Talmudic hairsplitting and Roman oratory help us to be fair and just? Given statistical evidence, like the fact that after correcting for crime severity, black felons are over four times more likely to be given the death sentence than white felons, I’m skeptical. The judges are still human, still full of prejudices and priors, (and still white), but we now have an obfuscation mechanism so that we can more easily pretend it’s not so. I don’t have a solution, but I’d say that if we’re interested in fair judgments, legal documents masquerading as first-order logic— the blind following the one-eyed, as it were— may not be the best starting point.

Someone I know, who spent summers in Lagos as a teenager, enthuses about the rule of law, because he has seen the horrors of opportunistic lawlessness. I agree, but it seems to me that by asserting that lengthy legal codes are the solution, we commit the same error that Fundamentalists do when they claim that atheists have no moral compass. Yes, a belief that one is observed and judged all the time by a higher power holding a book of laws will tend to constrain one’s behavior; but does the choice to constrain one’s behavior on moral grounds imply that one is religious? Even logic is good enough to give us the answer: (A→B) ≠ (B→A).