A few months ago, I drove past the corner of 5th and Pike in the evening and saw something new, a shopfront that flashing by looked like some sort of Babbagesque mechanical computer, brass machinery gridded in glass and lit goldenly from behind. I would have circled around the block to take a closer look, but was running late as usual. This was how I first experienced what is perhaps the most beautifully designed window shop display I’ve ever seen— and, shockingly, in Seattle!

Although the hundreds of vintage sewing machines in their windows did hold my interest for many minutes when I went back there to explore on foot, I was completely uninterested in what this shop actually sold, once I understood that it involved clothing.

This is because for more than a decade I’ve worn nothing but jeans, black T shirts, and black shoes. Family, friends and colleagues will confirm that this is very nearly not an exaggeration. The shirts are featureless, with no logos, writing or tags. The shoes are featureless too, with no laces. Their main property is that they slip on and off easily in the security line (Merrell World Traveler).

Why such a joyless apparel diet?— well, I just didn’t want to think about it. I find trivial choices difficult. Much better to just round down these aspects of life to their functional minima: pull a black shirt from the top of the stack of identical such shirts, ditto the jeans, and step into the shoes on the way out the door. In fact I felt very smug about all this, the smugness of outsmarting oneself by setting one’s watch just the right number of minutes ahead.

But I’ve been waking up, slowly and by small increments, to the possibility of clothes as a valid means of self-expression. (Yes, I live under a rock, bla blabla.)

In fact I began waking up a few years ago, when Adrienne discovered Eileen Fisher. (Not that she has ever been clothing-challenged like me.) This women’s clothes company makes really beautiful things. Their use of color is both sparing and intense. The fabrics are wonderfully textured, and the patterns borrow liberally from the visual language of other forms, things like scarves that fall like torn petals, wispily knitted jerseys that cling and billow like iridescent jellyfish, coarsely woven jackets that somehow feel like Japanese butterfly books. Yet unlike the distorted inhuman artworks one sees in fashion mags, these clothes somehow feel made to be worn by real people in the real world, by women who live and work substantial lives out there in heterogeneous environments that include people like— well, like me, in my jeans and black shirts.

I’m not entirely sure how this effect is achieved, but I think one key ingredient is a sense of tangible workmanship and solidity in the fabrics, the seams and the fastening systems. From this perspective, Eileen Fisher clothes are perhaps drawing from the same well as jeans. Jeans are so enduringly, universally popular, I think because their entire nature and construction emphasizes a sense of security in their integrity of form and function, in the context of a wide range of social and physical interactions with the world. In a good pair of jeans, one feels unfussy, ruggedized, ready for life. This is what is really meant by “comfortable”. The effect can be achieved with more delicate fabrics too, if the workmanship is robust and the context well suited.

I’m not entirely sure how this effect is achieved, but I think one key ingredient is a sense of tangible workmanship and solidity in the fabrics, the seams and the fastening systems. From this perspective, Eileen Fisher clothes are perhaps drawing from the same well as jeans. Jeans are so enduringly, universally popular, I think because their entire nature and construction emphasizes a sense of security in their integrity of form and function, in the context of a wide range of social and physical interactions with the world. In a good pair of jeans, one feels unfussy, ruggedized, ready for life. This is what is really meant by “comfortable”. The effect can be achieved with more delicate fabrics too, if the workmanship is robust and the context well suited.

The elegance of the leopard, both functional and beautiful, is more compelling than the foppishness of the peacock. Aside from my own issues, my discomfort with fashion comes from two intertwined evils, I think: first, that like peacocks, we’ve largely reserved external beauty for one gender— the other one; second, that the way we express beauty in women’s clothing seems so often to tend toward the peacock end of things. Transgendered peacock. Girl-peacocks make me uneasy because I mentally mirror their discomfort and lack of balance, rather than enjoying their fragility and the dubious sense of control that’s supposed to give me as a male. On the other hand socially acceptable beauty in (socially acceptable) male clothes is of such a subtle and contingent character, it makes me think of a bunch of hens critiquing each others’ dull brown plumage. Is James Bond’s suit and tie so much better than Dilbert’s? I suppose so, but it’s all shades of tedious, if you ask me.

The Asian jungle fowl, now that’s more my kind of chicken:

The Asian jungle fowl, now that’s more my kind of chicken:

How magnificent is that. My own experiments along these lines began in earnest with this pair of orange shoes.

How magnificent is that. My own experiments along these lines began in earnest with this pair of orange shoes.

I’ve found them to have a real effect on my sense of self and wellbeing in the world. People— strangers— smile at me more with these on. Even with no other elements, or perhaps especially with no other elements.

I’ve found them to have a real effect on my sense of self and wellbeing in the world. People— strangers— smile at me more with these on. Even with no other elements, or perhaps especially with no other elements.

Better jeans followed (Adriano Goldschmied Protégé, for what it’s worth), and other small things. Finally, Allsaints was brought back to my attention. The inside is as appealing as the outside, continuing in the same prewar/postpunk vein.

This store very much capitalizes on the values of denim culture. Hollis Henry surely shops here— though a turn-off for us both would be its fetishization of the “authentic”, including chemical treatments lovingly designed to mimic skateboard trauma, or the patina of several consecutive nights’ sleep in the gutter.

This store very much capitalizes on the values of denim culture. Hollis Henry surely shops here— though a turn-off for us both would be its fetishization of the “authentic”, including chemical treatments lovingly designed to mimic skateboard trauma, or the patina of several consecutive nights’ sleep in the gutter.

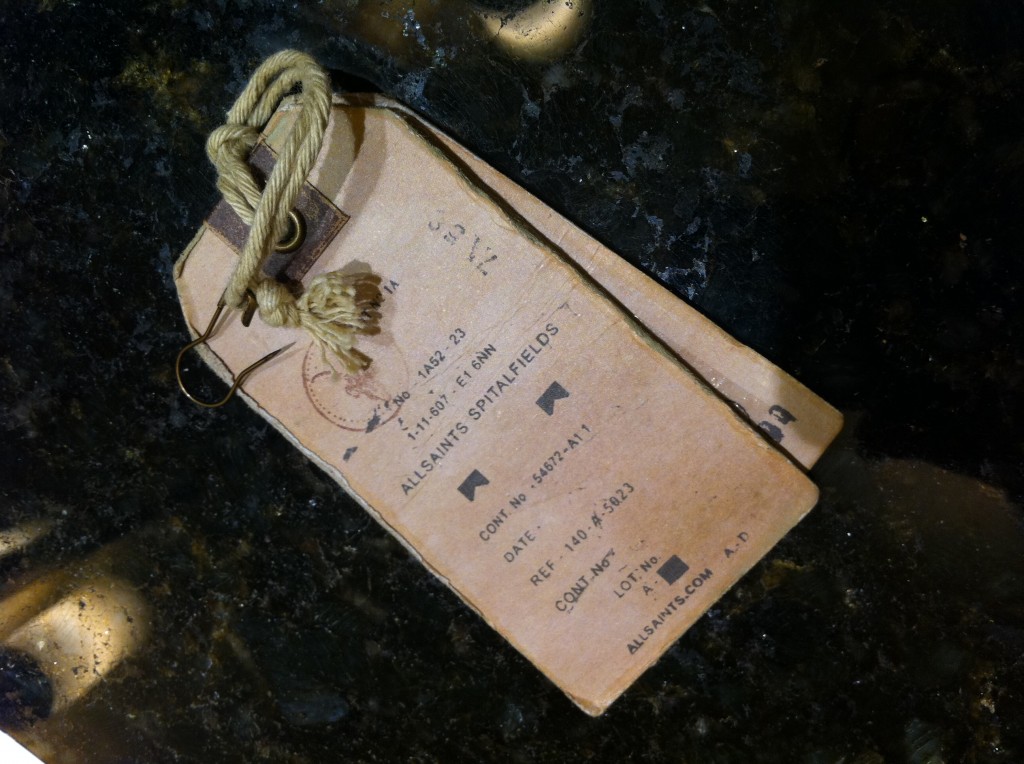

Still, Allsaints is as charmingly aspergersish in its approach to clothes as the shop display suggests, sort of like Bloc Party. Even the safety pins are custom-made.

The palette ranges from dirt, through certain oxides, to the neutral greyline, to blue, to just shy of white. The design language is constrained enough, and the materials and workmanship appealing enough, to make it possible for me to shop here without overloading my decision circuits. There’s a solemnly playful sense of “hoodie couture” about some of these things, e.g. the following object:

The palette ranges from dirt, through certain oxides, to the neutral greyline, to blue, to just shy of white. The design language is constrained enough, and the materials and workmanship appealing enough, to make it possible for me to shop here without overloading my decision circuits. There’s a solemnly playful sense of “hoodie couture” about some of these things, e.g. the following object:

Although at first glance it might appear to be made for another species, in fact that tubular head structure piles up into a sort of hybrid between hood, turtleneck, scarf and.. ruff.

Although at first glance it might appear to be made for another species, in fact that tubular head structure piles up into a sort of hybrid between hood, turtleneck, scarf and.. ruff.

3 Responses to allsaints